Dear reader,

While this post discusses fiction as a vehicle to transmit a powerful message that can lead people to take action, it contains spoilers on Netflix’s show Adolescence. If you haven’t watched it yet, you may want to revisit it later. Although given how much media attention the show has captured -for all the right reasons- there’s probably little you don’t know by know.

The final year of my undergraduate degree1, which I spent in the US, I became friends with a girl from El Salvador.

We had a couple of classes together and united by our common language, the by-product of my ancestors’ colonial antics, we quickly bonded over the one thing that has always been a green flag in ascertaining potential friendships: food. It was during a meal at her house, where she was preparing home-maded pupusas2, that she revealed a dark secret that could have put an immediate end to our friendship.

“So what kind of books do you like reading,” she asked as she flipped the pupusas on the pan and I inspected her bookshelves.

“I’m quite eclectic in my taste. The important thing for me is to find a story I can get lost into.”

“What do you mean a story? What do you need that for?,” she asked with a tone of genuine surprise in her voice.

“Well, that’s the basis of novels, isn’t it? So what I mean is that as long as it’s one I find a way to connect to, I don’t really care much for genre or authors. It’s about the power of the writing to transport you somewhere else and help you see things from a different perspective.”

“What?,” she was truly dumbfounded by my answer until something seemed to click inside as she said, “What I meant is which kind of real books you like reading? Like serious books from which you can actually learn something. For instance, I’m currently reading a psychology textbook because I want to understand the human mind better. What about you?”

What ensued was a fascinating conversation on why she was of course wrong writing off fiction as useless while I defended its capacity to help us look at the world in new ways, become more empathetic, and even learn useful facts and lessons. In fact, if my friend had bothered to read American Psycho, she would have known that Patrick Bates gives the DSM manual3 a run for its money and therefore Bret Easton Ellis’ novel is the only reading you need to recognise psychopaths from afar. If that’s not useful and practical information I don’t know what is.

I eventually agreed to disagree because someone has to be the bigger person and in this case the circumstances dictated it had to be me. I hadn’t come all the way to my friend’s house to leave on an empty stomach over a difference of opinion on books. I knew I was right and that’s all that mattered to me while I stuffed myself with one hot pupusa after another.

Over the years I’ve heard several times a similar reasoning from so-called serious readers (their words, not mine), whose argument against fiction are usually along the lines of why waste time with made-up stories when non-fiction is a straight route into acquiring vital information which can be instrumental in helping us make decisions and take action to find solutions for real problems with facts and data in hand.

Nothing against a well-informed non-fiction reader - I’m among their ranks myself on more levels than one. However, absorbing facts isn’t all that is cracked up to be when it comes to understanding a situation, and its potential consequences, because it lacks a key component that will ultimately connect the dots and may even push us to take action. Emotion.

Any mediocre marketer knows that in order to get people to care about something you need to move them. That’s why there’s a scene in the award-winning Derry Girls4 where the character of Claire is raising money to support Kamal, a poor chap from Ethiopia who has to walk long distances to get to drinkable water, instead of for a whole population that may have been devastated by war. A real child that is an innocent victim is arguably more relatable and useful for her fundraising efforts than a faceless number of casualties, no matter how high or accurate that figure is. NGOs have long known this and used it on Claire for their benefit.

This is precisely how storytelling and fiction can be a powerful vehicle to pass an important message across in a way that captures our attention and, more significantly, make us care and take action.

Adolescence, the Netflix four-part series co-written by Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham (who also stars in it) is the latest example of how a well-crafted story inspired in real events can open the door for a debate about an issue that is impacting people’s lives.

In case you aren’t familiar with it, this limited series tells the story of a 13-year old boy, Jamie, who stabs to death a female classmate, Katie. This is revealed on the first episode because the purpose of this story isn’t to find out who has committed the crime but to help us understand the motive as well as the many ramifications this action has beyond the obvious loss of an innocent person’s life.

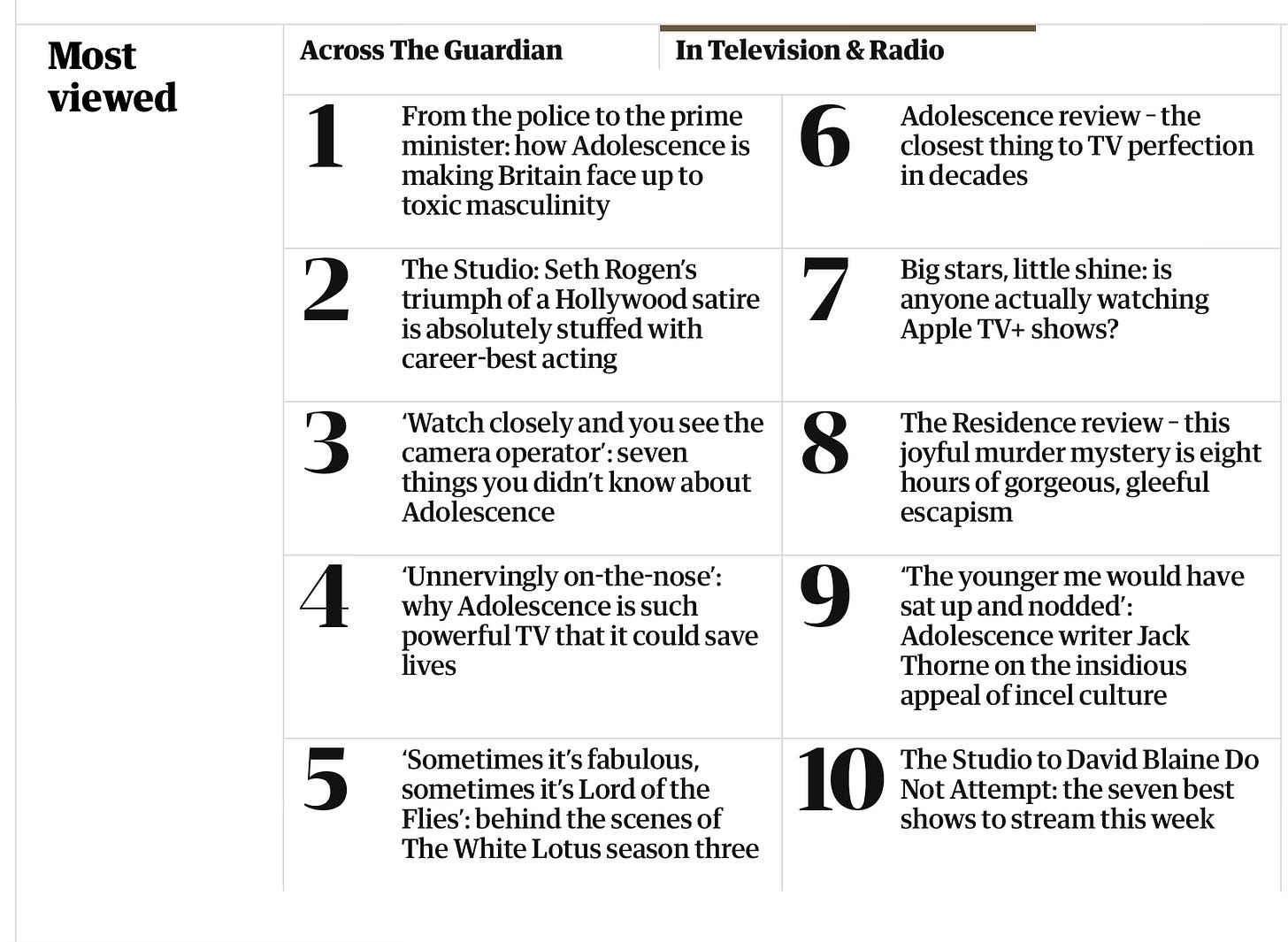

Much has been written about Adolescence already, which has received overwhelming critical and public acclaim in the UK in ways that seem unprecedented in this era of fragmented content consumption, including record ratings. Leaving aside the terrific acting from everyone (with an impressive Owen Cooper in his acting debut, no doubt a rising star) or the technical prowess of the one-take episodes5, the real triumph of this series is to use storytelling to tackle two serious problems that are very much making headlines on a regular basis in the UK: the rise of knife crime among young people and how to keep children and young people safe online.

In fact, the original idea for the show comes from a couple of stories Stephen Graham read about a young boys stabbing young girls and he decided that this was something worth exploring and talking about to understand better the underlying causes beyond the headlines.

For Adolescence Graham and Thorne have specifically concentrated on how the unsupervised access young people have to the internet, via smartphones and social media, intersect with the rise of the manosphere and toxic male influencers online fuelling the growth of misogynistic and anti-feminism attitudes among young boys.

He puts Jamie, a young boy from a good, hardworking family, at the centre of the narrative as the crystallisation of how these messages can find their way to anyone and why that is extremely dangerous for young people, whose online lives and identities have come to define them as much -if not more- as their offline ones in unprecedented ways, especially after the pandemic where they suddenly found themselves cut off from friends and relying on social media to keep in touch.

Because that is the core message of the show: for the first time in history there is an abyssal gap between the way adults experience reality, anchored mostly in the physical world, and the way young people do, giving the same level of attention if not more to the digital spaces in which they are socially active, where they are likely to find dubious figures who may not have their best interests at heart and who may go under the radar of the adults in their lives.

As a child, when I was left to my own devices to play on my own or with my sister or cousins, everyone knew we weren’t doing anything dangerous or harmful even though they weren’t keeping an eye on us.6 My hobbies included reading, writing, drawing, and mostly creating imaginary scenarios in my head that involved me riding a fig tree in my grandparents’ house pretending it was a unicorn called Rayo de Luna. All very demure.

As a teenager I was still pretty much safe when not under the anxious eye of my mother. While I kept reading, writing, and drawing, I swapped fig-tree riding for bike riding (without any falls to report), playing basketball, catechism classes, (all my close friends went - it was that or folk dance and I was born without an ounce of rhythm), and of course watching Inspector Rex religiously every Sunday afternoon. This was often met with a frown from one of my friends who couldn’t understand that I preferred a dog to hanging out with her, which always amused me because at 16 it was obvious I was far more interested in Gedeon Burkhard, who played the lead in the series7

Even when they may not have shared my interests, my parents and grandparents could easily assess whether they were dangerous or represented any risks because our way of living hadn’t been massively disrupted in the previous generations. Books had been around for centuries, basketball and bike riding for decades, religion since AD, make-believe play is immemorial, and crushes on fictional TV characters in a country infested with telenovelas and their dashing-looking Latin American actors were hardly a sign of concern.

Nowadays, parents can be cooking dinner in the kitchen while their kids are abusing someone/being abused online from the safety of their own little bedrooms and the convenience of their smartphone, which is a rather chilling thought because it can perfectly go unnoticed while happening under their nose. In the era of smartphones and social media, the notion of play and socialising has been disrupted and shifted from activities that required engagement with the physical world to online interactions that can happen indoors. And yet being physically at home no longer equals being safe.

This parallel online world inhabited by young people may have come as a shock to viewers, especially adults with kids for whom the show rings very close to home, and yet the average adult spends over four hours online per day, inevitably comparing ourselves -our bodies, our faces, our lifestyles- to others and relying on the advice of total strangers that go by the name of influencers. Why does it come as a surprise then that young people do exactly the same, with the added risk that they are even more vulnerable to external judgement and how they’re seen by peers?

Adolescence has in fact made me reflect on how blessed I was to grow up in an internet-free era in a small town, where one had a proper check-and-balances system in place that was very grounding. It was ok to be naughty and behave like the teenager you were, no one expected otherwise, but there were also limits and people enforced them to make sure you turned out alright as an adult.

If you talked back or responded rudely or treated people badly without reason, there’ll be someone giving you a sense-check8 whether an adult who knew you, a teacher, a relative, a parent or your own friends. Being called out for poor behaviour was a reason for shame, perhaps because we couldn’t escape to an alternative reality and pretend to be different than we were. Adolescence however sheds a light on something that I’ve been hearing often in a work context for years: how young people don’t really distinguish between their experiences in the physical and digital worlds as the line between the two is more blurred for them than for adults who have grown up in the pre-internet days.

In the series we learn that Jamie stabs Katie because she has accused him of being an incel on social media through the use of coded emojis that seem inoffensive to adults (to the point of being mistaken for a friendly exchange between the two) but whose true meaning is clear to peers.

In Episode 2 the disconnect between the current adult and teenage online experience is obvious through a scene which reveals the real meaning of these messages and the influence of the manosphere and its unfounded dogmas (like the 80/20 rule). When Adam, the son of the main detective on the case and attending the same school as Jamie, tries to explain the true meaning of these social media exchanges, his father dismisses him as first, a poignant metaphor of the disconnect between the two characters and the worlds they live in.

When we finally understand that Jamies’ reputation has been compromised online, where anyone who matters to him can see it and judge him, his motive for stabbing Katie becomes more obvious. Little does it matter that Jamie can’t really be an incel at 13 and that any adult would confirm as much, offering reassurance and perspective to counterbalance an online narrative with little significance or resonance offline. For Jamie his reality is as digital as it is physical and being attacked in his still nascent ideas of masculinity and ridiculed online has fatal consequences offline.

This is another reason for which I’m grateful I grew up in an internet-free world. We could figure out things at our own pace and didn’t need to become adults before our time. We were incessantly told to distrust anyone we didn’t know and offered us anything, and there was the odd girl who became pregnant at 16, but most of us were mostly uninterested in sex until we went to university. The most shocking thing I remember seeing as a teenager was a magazine with women showing their tits (they had knickers on, we weren’t pervs) which someone had brought to school. We only had time for a quick look before a teacher came and confiscated it during recess.

This doesn’t mean sexual content wasn’t around, but it wasn’t as available or unnoticeable to consume as it is today as it had to materialise physically. Whether it was a VHS tape or a magazine, it left a trace that could be easily tracked back to the owner. Back then, if someone accused someone of something it was far more likely of being a bit too obsessed with sex if they as much as hinted at it, which wasn’t seen as a positive trait in either boys or girls. I remember a classmate once told us she had been allowed to see Pretty Woman when it was on TV and we were in awe because our parents changed channel the moment two people kissed and proceeded to send us to bed with immediate effect.

I compare that shielded upbringing with how available everything is now to young people, how exposed they are through their phones to content they are too young to process but which can damage their self-esteem and warp their concept of sexuality, taking away their innocence far too early. Not to speak of how peer pressure to project a certain online image when they’re still figuring out who they are can further isolate young people and leave them vulnerable to manipulators. It’s no wonder we’ve seen some worrying headlines in recent times highlighting the brave new online world children and teenagers have to navigate in addition to the physical one.

Whether is deep-fake images of girls generated just for fun, the secret hashtags teenagers use to post about self-harm, the rise in cyberbullying and its fatal consequences, exposure to pornography at an early age, being at high risk of being scammed or falling prey of sexual abuse or exploitation, there is no lack of potential iterations Stephen Graham could have chosen from for creating a show about the many ways in which children and teenagers are at the mercy of technological dangers these days.

One of the strongest points of Adolescence as a powerful piece of storytelling is that it has crafted a relatable narrative that has elicited a strong emotional response in people to a reality that has long been represented in the media with faceless facts, figures and which left many indifferent to its real impact until seeing it play out in the show.

Stephen Graham and Jack Thorne must have understood as much and as creators of the show they have given the public a very specific individual story affecting young people these days to talk about a bigger issue at play that has made anyone with kids, or who is in contact with them regularly (teachers, educators, doctors, psychologists, coaches, etc) to ask themselves whether they are doing enough to protect them and offer positive alternative role models they can seek advice in and look up to.

While it shouldn’t be the work of fiction to advance the necessary legislation, the reality is that the show has caused a stir and from parents to parliament (PM Keir Starmer included) everyone in the UK is now talking about how to prevent toxic masculinity from sipping through the digital cracks, prompting a debate on smartphone use and whether there should be a social media ban for under 16.

Despite studies confirming that teenagers’ mental health worsens with the use of social media Big Tech companies know that younger audiences are far more likely to remain loyal to a platform so the sooner they start using it, the less likely it is they jump ship to another, which means they are potential clients for whatever new products are rolled out and therefore less interest in introducing age bans.

Hopefully these conversations prompted by a fiction show will help people to reframe news headlines and put them into context when they read about the Digital Safety Act, the EU’s content law that tackles the spread of illegal content and information manipulation, and the Online Safety Act, which was approved by the UK parliament in 2023 to safeguard children from harmful online content but only fully in place since 17th March 2025.

Perhaps the most significant element of Adolescence as a powerful example of storytelling to translate headlines into relatable human experiences is the clever non-judgemental approach and the choice of showing the devastating ripple effects of the crime committed by Jamie on his family.

While the show largely ignores the main victim, and even addresses how victims are usually forgotten while criminals are exhaustively analysed and talked about in an attempt to elucidate their motives, and that is the case in the series where we learn next to nothing about the victim, the intention of Stephen Graham and Jack Thorne is evident.

The show wants us to realise that Jamie is not a monster, but rather a victim - in this case of a perverse online culture and the toxic masculinity ideals that have led him to act on behalf of an agenda he’s far too young to understand, least of all able to refute. And so are his parents, who despite having to deal with the devastating emotional aftermath and shock of the crime their son has committed is also subject to public scrutiny, held no doubt as the true responsibles for Jamie’s atrocious act.

By putting the family at the centre of the last episode, by giving us an opportunity to witness their life without Jamie and the many questions the parents ask themselves while also trying to be present for their daughter, the audience can fully appreciate the spillover effect of a young person committing a crime and the many lives that can be destroyed in one single act. The message is loud and clear: withhold judgement because everyone loses when something this terrible happens and we are collectively responsible.

Adolescence may focus on the dangers of the manosphere and toxic male influencers, but it transcends it to signify something bigger. It’s been said that the show doesn’t offer a final answer for the problems it wants to bring attention to, but I disagree. The show succeeds in highlighting the importance of making sure we have the right tools not only to protect young people online, but also to connect with them offline, in the family as well as at school, offering them alternative positive role models to the dubious figures they come across on social media, and ensuring they feel part of a community and have a physical checks-and-balance system they can resort to to keep them grounded when the digital world starts distorting their vision of reality.

If a fictional limited series has managed to help us realise as much and provoke a national conversation on the urgency to fight the rise of online misogyny and toxic masculinity so a new generation of young people can be raised on empathy, emotional vulnerability, resilience, respect, and love for themselves and each other, it means that fiction is after all an invaluable tool to help us take action to change our reality by infusing life into otherwise faceless facts. By extension storytelling is not only necessary but indeed vital to help us shape a better world through the power of shared human experiences.

Abroad is independent publication about London, living in between cultures, languages, books, music, films, creativity, and being human in the age of artificial intelligence.

If you enjoy my writing, the best way to support it is by liking, commenting and sharing it so the algorithm can inflict my thoughts on a greater number of people, which has been a childhood dream of mine.

If you find yourself here regularly, you can be part of the Abroad journey by subscribing for free to receive updates.

English for convenience and relatability to the anglo-american system but in reality a 5 year-long course of studies comprising a mix of foreign languages, literature, linguistics, translation, contemporary American art and even history of urbanism. I’ll do it again if I could.

A common culinary delicacy across several countries in Central and South America, which in fact is known as arepas in Venezuela and Colombia.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the sancta sanctorum of diagnostics for the US medical profession but also widely used internationally.

Another excellent example of how storytelling and in this case comedy are put to good use to talk about a complex and violent historical period.

When I knew about this and that Stephen Graham was on the show, his extraordinary performance in Boiling Point, also shot in one take, came to mind. Both the film and Adolescence have been masterfully directed by Philip Barantini.

There is of course that time when one of my cousins decided to learn to ride a bike in my grandparents’ courtyard, fell in the most absurd way while being still on the spot and ended up in hospital with a broken tibia.

For accuracy there were different male leads in Inspector Rex and every time one of them got replaced it was a bit of a drama at home because we couldn’t imagine the show without them, but the arrival of Gedeon was very welcomed. Considering the show run for 17 years, there were probably different dogs as well but I noticed a bit less, to be honest.

Which may come in the form of a very serious talk or mild physical violence that did the trick and kept you out out trouble for the foreseeable future. I’m not saying it was a perfect system.

It’s a tough situation right now for parents because you want to protect your kids without making them feel different from their peers as that could backfire. I don’t know what the solution to growing use of phones and social media can be, but having an awareness of their impact in young people is a good starting point.

What a fantastic, well written, researched and thoughtful article!! Thank you!!! I agree with your assessment about the importance of fiction as well as the truth and impact of the show Adolescence 🤯 which contains brilliant writing, acting and filmmaking.