False Friends

The English language has an extraordinary capacity for elegant deceit in plain sight.

“So what do you think?”

“Not bad… it’s, er, a bit dry outside, but, ahem, moist in the middle,” this last sentence has come out a bit muffled in between coughs, presumably caused by the accumulation of hard and semi-liquid components inside the mouth of Colleague Number 1.

“And you? You like it?”

Here we go.

Why do I put myself in difficult situations unnecessarily when I could have dodged this bullet with a simple “no, thanks”?

Instead, here I am, unable to send down the most disgusting cake I’ve ever eaten and which is both uncooked and overcooked in a way I never knew the laws of physics and baking allowed. I guess this is how innovation happens but I never thought I’d be at the forefront of it. If at least the flavours -any flavour- were there I could somehow ignore the hybrid liquid inside/rock hard outside texture, but instead this is the closest I’ll be to eating wet sand voluntarily. Because I did this to myself. No one forced me to say, “Is that cake?”, which we all know means, ”Can I have some?”

And now, while Colleague Number 1 is getting worryingly red and her eyes have become teary as she is holding her breath while trying to send down whatever we have naively mistaken for cake but which will be clearly referred to by future colleagues as the cause of our death, I need to find the words to convey my disappointment at this deceit without being offensive or accusing Colleague Number 2 -who has baked this monstrosity- of involuntary manslaughter.

“Yes, it’s quite dry,” I manage to blurt out, crumbs spluttering out of my mouth, falling violently on my desk and hitting it like hail on pavement, while my head is slightly tilted sideways to avoid 1) overspilling the more liquid bits as I open my mouth and 2) choking on both the solid and liquid particles I’m juggling as I speak.

Realising my mistake immediately, and that I must look like someone suffering an epileptic fit to everyone except Colleague Number 1 -provided she’s still alive and breathing-, I add something quickly that can satisfy Colleague Number 2, send her off to offering her deathly concoction to other colleagues, release me from this pathetic pose, and allow Colleague Number 1 and myself to spit it out as soon as Colleague Number 2 turns her back on us. Hope it’s not too late by then.

“But I don’t hate it.”

Bingo.

I don’t hate it. Of course.

What I love most about the English language is its capacity for elegant deceit in plain sight.

I. Don’t. Hate. It.

The magic words that save you when you’re openly confronted and must come clean without offering any positive reinforcement nor being openly critical of something for which you nurture a deep, visceral, and without a shadow of a doubt irreversible, disgust.

Don’t you ever make the mistake of thinking “I don’t hate it” it’s a neutral expression for it’s definitely not. How many times have you used it for something you don’t strongly dislike but definitely don’t like?

My thoughts exactly.

There is one fascinating element about learning a language, any language, that many people often disregard in their pursuit of getting rid of an accent or mastering the French subjunctive (abandon all hope in both cases) and that is the pragmatics of it.

As someone who has been both a learner and a teacher1 of several foreign languages, I can tell you that pragmatics is where true mastery of a language, our own or a foreign one, lays.

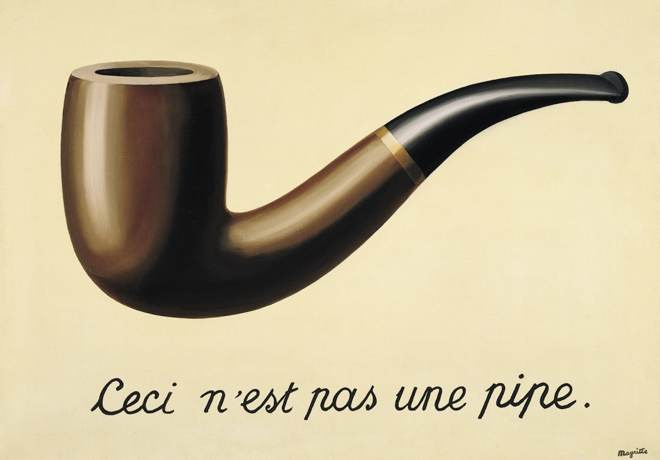

Without bothering you with a linguistics lesson, pragmatics is a branch of linguistics that focuses on what is being said and what is being implied, which is at the basis of fluency and command of a language beyond first degree meaning. It is, with the permission of Ferdinand de Saussure2, where the signified and the signifier really come together in mysterious, and often rather confusing ways.

To put it simply, pragmatics is to language what a wheel is to a car.

It’s what helps you steer it in the direction you intend to go without crashing or causing collateral damage. It’s what help you avoid a frontal collision by saying “Yeah, that was fun. We should do it again,” when what you actually mean is, “Let’s not go through this ordeal anytime soon, I implore you.”

That’s universal.

Everyone knows that’s how you politely put an end to repeating something you didn’t want to do in first place but can’t openly say because there’s no need to be rude and no one needs to get hurt. Or see each other again. Please. It’s taken me 15 years to memorise my number. I can’t change it now.

In every day life, pragmatics is at the heart of many of our interactions, where it acts as a functional tool to get people to do things for us without explicitly having to ask.

When someone says in English, “Isn’t it a bit hot in here?” is not only a way for them to test whether they’re peri-menopausal, but a veiled invitation for someone else to open a window because the person asking is A) probably hot and B) too lazy to get up and do it themselves.

Now, if those nearby respond with, “Would you like me to open the window?,” congratulations, the message has achieved its intended purpose.

If, instead, they respond “No, I’m actually quite cold myself,” then the subject originally asking is most likely surrounded by non-native English speakers.

Because, and here I’ll be very honest with you, what in the name of the king of double meanings that Shakespeare was do British people actually mean most of the time?

I stand by the belief that non-native speakers learn a language twice.

The first time to be able to communicate, for which they have to learn vocabulary, verbs, syntax, whether the washing machine is feminine or masculine, and unless they’re lucky, a huge amount of exceptions for any of the previously listed elements.

The second time to actually understand what people mean when they speak when using the above vocabulary, syntax, and verbs. And it’s not exactly the same thing.

This is a surprising discovery that only hits once non-native speakers have gone through the first learning process and have enough linguistic acumen for them to have proper conversations in the present, past and future beyond, “Why did you do during the weekend?,” or “Why do you think you’re the right candidate for this job?.” In fairness either of these questions would deserve its own analysis of what actually people mean by them and how they should be answered.

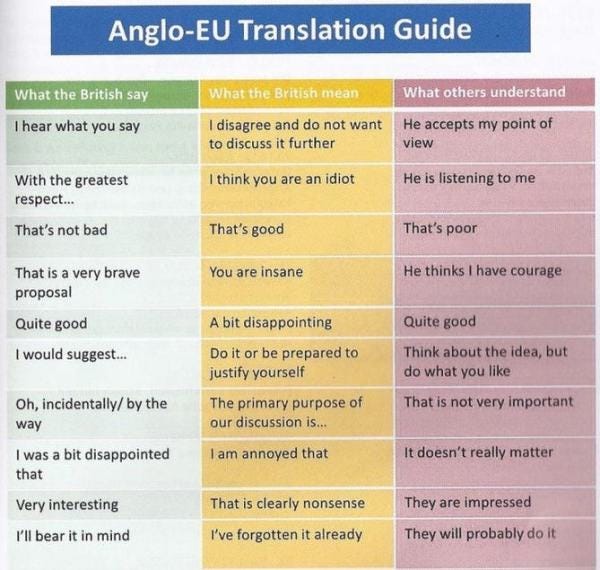

And while all languages have a level of pragmatics that speakers learn to navigate eventually, British English, however, is particularly vicious in its lack of correlation between what comes out of someone’s mouth and what it’s going on in their minds. Therefore a good grasp of English pragmatics is essential to avoid linguistic pitfalls and end up in undesirable situations because as a non-native speaker you made the foolish assumption of thinking that “quite good” really means just that.

This way of speaking probably comes from British people conforming to the stereotype of being polite and fearing offending others, so it follows they are reluctant to express themselves in ways that could invite open confrontation.

Although you could argue that a country whose Queen encouraged, and even protected, Francis Drake to openly attack Spanish ships and ports to rob the hard-earned gold my ancient country men fought so hard to obtain by decimating whole civilisations with extenuating forced labour is not precisely the image that comes to mind when thinking of non-confrontational people. It had to be said.

Letting that historical episode aside, the XXI century British citizen is mostly conflict avoidant. Be it because society has evolved and ransacking others for what’s theirs is frown upon, be it because Brexit has achieved a similar purpose anyway by robbing European people their freedom of movement, the thing is that the average British person will avoid speaking their mind openly if they can help it.

Which leaves you, dear non-native English speaker, drowning in a sea of linguistic doubt and confusion. But you’re not alone.

When I moved to my current job, and despite having lived in London for seven years already plus a couple more spent in the US as well as stays in Ireland and Scotland, it took a while to get used to what was actually happening in meetings with British colleagues.

One moment we would be all laughing and sharing a joke about what someone had said, and it was all fun and games with plenty of “that’s actually quite a brilliant idea” and “I think we can work on that” thrown away like confetti, and post-meeting all that contained exhilaration turned into hushed conversations and reassurances that “of course not, don’t be ridiculous, no one actually thought that idea could go anywhere.”

If you’re British, I hope you will excuse my bluntness but I found it very confusing. Not to mention a waste of time.

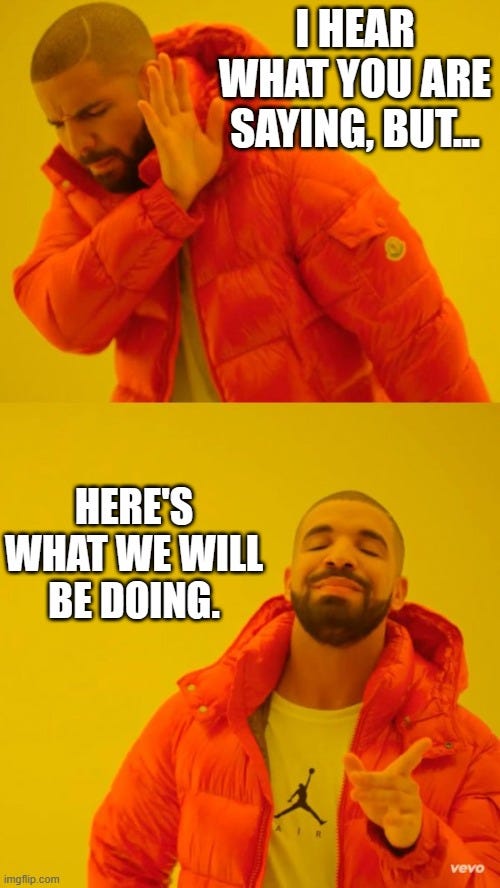

Why could no one simply say, in a polite but clear way, what they really thought, especially when they wanted to express their opposition and they had good reason to do so if that could save everyone’s time and work?

Or knew there was no point in continuing a conversation with someone that would lead nowhere but not stating it openly would only lead to repeating the same conversation ad infinitum?

Or indicating to others when a person is shady and it would be best to avoid entertain them in any way, shape, or form?

Instead, the “I hear what you’re saying,” “Let’s sleep on it for a bit,” and “He doesn’t often deliver what he promises,” quickly became part of my vocabulary even though I couldn’t quite grasp their full meaning. I simply learned, as one often does with linguistic exceptions that have no logical explanation, that it was best to memorise them without overthinking them too much.

This was a sharp contrast with the “This is the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard,” or “Listen, let’s not waste more time with this: we’re not interested,” or “Be careful with this person, he’s dodgy as fuck,” that were exchanged with generosity and best intentions among my European colleagues. This was their way of saying, “We’ve been there, too. But don’t worry, we’ve got your back.”

These were my people and they spoke my language. Not only the one I communicated in when I opened my mouth, but the one I used when I wanted to make sure others had understood what I meant.

These were colleagues to whom I could say “fine” and it meant “fine”, or “I don’t like it/You’re wrong/That’s ridiculous,” and it meant “it’s not a personal attack, I just don’t like this/you’re actually wrong/this is very ridiculous so I’m letting you know.”

On the basis of our brutal honesty and shared puzzlement for the incomprehensible language British people around us used for fear of a linguistic faux pas that could lead them to speak their mind if they weren’t careful, we forged indestructible friendships.

This linguistic alliance has emboldened us and we are also determined to introduce the concept of “say what you mean” in the minds of our British colleagues like solid foods in the diet of an infant, one direct expression at a time, paying attention to how they reacted when digesting it.

Whether in a work setting or the comfort of the home, we have finally realised the best medicine to force British people to speak clearly is to use the English language to our advantage to cut short the possibility of entertaining the kind of soul-crushing conversations our British counterparts delighted in repeating over and over because no one dares utter the words, “This shit doesn’t work.”

“I have this client that I was always trying to speak with,” a European friend from work said to me one day, “and it had taken us a long time to find a time when we both were available. I had suggested we did a call, but he insisted he wanted to meet in person. And it was weird because he kept cancelling every time we put something on the diary and the date got close. Anyway, I arrive at his office, which took me almost an hour to get to, and after 15 minutes, the guy goes ‘I don’t want to take anymore of your time, so I’ll let you carry on with your busy day’.”

“Oh wow, that’s weird. What did you do?,” I asked in shock.

“I know these people, I’ve lived here 20 years. They never tell you, ‘I don’t think we need to meet’, do they? I find that a bit annoying, to be honest. Why can’t they speak like normal people?” she asked as we both laughed at the crazy idea of how a straightforward British person would communicate.

“I guess we have to pick our battles,” I responded.

“My in-laws are the same, they never tell you clearly what they want from you. Every time we visit is ‘wouldn’t it be nice to have some tea and toast?’ whenever I’m going in the kitchen,” she added with an eye roll and a sigh of disbelief. “Anyway, it had taken me an hour to get to this guy’s office and I couldn’t do much with my day after that meeting. And to be honest with you, I was a bit pissed off because he was the one who had insisted on meeting in person and never made it clear he actually didn’t want to,” she continued as my curiosity was growing. “So when he invited me to go, I checked my watch and I thought that if I left then I’d be getting straight into rush hour, so I may as well stay longer.”

“So what happened then?”

“When he said ‘I’ll let you carry on with your busy day,’ I looked at him and told him, ‘Oh, don’t worry about me. I have nothing else to do. I made sure to clear my calendar so we could have a proper conversation. I thought it’d be nice to have a coffee together, seeing it’s taken so long for us to finally meet,’” by now she was really enjoying herself and her eyes were sparkling with excitement.

“No, you didn’t!” I exclaimed in a mix of awe, incredulity, reverence, and endless admiration.

“Oh yes, I did,” she managed to articulate in between laughs. “If he didn’t want to meet me, he should have just said so the first time I asked, but because he kept cancelling last minute and suggesting another time to meet, I thought he was actually busy but wanted to meet. In the end I realised he was only agreeing out of courtesy and neither of us needed to be there. The thing that bothered me most is that he thought he could get rid of me in 15 minutes and I’d be fine with it. Wrong, mate, that’s not going to happen,” this came with a twang of Cockney for some reason. “But you know British people. They'd rather cut off an arm than tell you what they really think.”

“What did he say when you told him you didn’t have to go?”

“He went very pale and couldn’t speak, you know. At first I thought he was having a stroke but then I realised he probably wasn’t expecting me to be so direct,” her delight in the retelling of this meeting was palpable as she was choosing carefully which bits to feed me and at what pace to keep me hooked.

“And???? Did you end up having coffee at the office?”

“Noooo,” she said as her left eye gave me a cheeky wink when the reverberations of the last ‘o’ vanished. “He took me out for an afternoon tea nearby because he said that he wanted to thank me for having come all the way and was very happy we finally found a day that worked for both,” she said as we both exploded in an uncontrollable fit of laughter.

“Serves him right for not telling me to piss off straight away,” and after she uttered these words, I decided I should live by them from now on.

With the fresh learnings from my friend’s experience on my mind, when Colleague Number 2 materialises again out of nowhere by my desk with a plate of god knows what new inedible creation that defies the laws of logic and baking, I know I won’t fall into her trap for fear of confrontation, so I’m determined to use the power of open communication and plain English.

And so when she asks, “Would you like to try this cake? I’ve made it myself,” my voice doesn’t tremble.

“No, thanks, I’m not a big fan of wet sand. Good luck, though.”

She gives me the kind of look often reserved to someone who is clearly out of their mind, but you can’t openly call crazy because, remember, you’re British. For once it is nice not to be the one puzzled.

“That’s… interesting,” a fitting response in line with the canon of approved British answers for this scenario. She then squints at me briefly before turning her back and making her way to her next innocent victim.

As I observe her move from desk to desk, I feel sorry for the colleagues whose innate Britishness prevents them from refusing her offer and one after another end up going through the ordeal I experienced a few weeks ago in the company of Colleague Number 1, who now that I think about it I haven’t seen since then. Maybe she’s just quit. Probably easier than confronting again Colleague Number 2 when she comes around with her plate of deathly hallows.

It’s in that moment that the penny drops.

Colleague Number 2 is a sadist who relishes in watching people fight for their lives trying not to spit, swallow, breath and least of all offend while confronted about their opinion of the mixture they have been most kindly offered and graciously accepted of their own free will.

I bet she feels invincible knowing that no one would ever dare telling her she should get a restraining order if she ever comes close to an oven or a package of flour.

I wonder if she is thinking about the reply I have given her - surely a stark contrast to what I suspect is mostly unanimous agreement and positive feedback, reinforcing an absurd vicious baking cycle that no one feels strong enough to break. If only someone had the courage to state the obvious when presented with Colleague Number 2 creations and just said, “What in Colin the Caterpillar is this jarring piece of carbs?”

As I’m ready to leave and I’m packing my things, I notice there is someone standing behind me. Colleague Number 2, to my horror, has returned. I give a little jump, startled by her unexpected closeness.

“Sorry, I didn’t mean to scare you,” she seems sincere. “Just wanted to ask you something.” Now she looks down for a split second as she thinks about how to let out what she’s come to tell me. I can see there’s something she’s dying to know, but I am in the dark as to what it can possibly be.

“Is ‘wet sand’ a type of cake from Spain by any chance? Never heard of it before.”

I knew it.

The idea that I could have meant what I said was far too radical for a British person.

But don’t let me keep you any longer with my ramblings on the pragmatics of the English language. I’m sure you have a busy day ahead of you and lots of things to catch up with, so I’ll let you go now.3

Abroad is an independent publication about identity and belonging, living in between cultures and languages, the love of books, music, films, creativity, life in London, and being human in the age of artificial intelligence.

Thank you for reading Abroad!

If you enjoyed reading this post, like, comment and share as much as you like as so other can discover this publication as well. And if you find yourself here regularly, consider subscribing to receive updates and support my writing.

I doubt anyone learned much, but I needed the money and I spoke the languages, so what’s a foreign student got to do but shrug and say “it is what it is” when someone asks why the milk is feminine in Spanish but masculine in Italian?

The God to which linguists pray. A man who didn’t wrote a sentence and still managed to get a book published posthumously that is not only in print over a century later but also widely read, Course of General Linguistics. Fucking idol Ferdinand de Saussure.

Translation for non-native speakers: “Jesus, get a life. Can’t spend all day entertaining the lot of you.”

And here I was thinking Brits were so charmingly bantery and easy to understand haha!

In my experience living in the US, Americans are an amped up exaggeration of the Brits depicted here, with everything being maniacally AWESOME, nothing sincere ever said and everything being taken literally all the time.

The part about being hot in a room was hilariously recognizable – countless meetings at schools, events etc where you can almost feel people’s teeth chatter as they clutch themselves with bluing fingers but no one says anything until you the foreigner ask if they can turn down the AC. I continue to be surprised by a certain prevalent conformism in the Anglosphere.

There is so much more to language than just the words and the meaning isn’t it. Language is formed in and by culture so without understanding culture it’s so difficult to really “get” what people mean. It also took me a while to adapt to British working culture, especially them writing 7 paragraphs just to ask or convey the simplest thing! Though in the end I came to appreciate and enjoy the passive aggressiveness of writing things like “Not sure if you’ve had the chance to read my email following your request for information “. Anyway from the title I thought you were going to write about similar words with different meanings in languages. I was looking forward to the embarrassed/ embarazada joke 😂