Does Substack have a Musk and Zuckerberg problem?

Welcome to the 2025 iteration of Substack's views on free speech and the US government strategy to make users' data great again.

Me again, hello. Yep two post in a week after a month of radio silence.

Because this publication is about many things but mostly living in London, cultural differences, languages, books, music, films, creativity, and being human in the age of artificial intelligence, today I’m writing about the latest.

Or more specifically about tech meets politics to analyse a recent turn of events that has got me thinking about Substack’s future direction of travel after its cofounders’ recent statement about Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg and what it means under the pro-AI innovation (read anti-regulation) Trump administration.

If you aren’t that keen on the subject, and because this is a very long post, I won’t take it personally if you skip it. In fact I won’t even know. However, and in case you may have missed any previous posts, maybe you want to check out Spanish Christmas explained in three ads, my thoughts on the Pelicot affair or the latest Culture Fix edition.

If you’re sticking around for the tech talk, get comfortable and enjoy the ride.

People always say it’s not about the destination, it’s about the journey but I have always suspected this came from someone who was travelling first class, probably to their dream holiday spot, no expense spared.

I’m more of the opinion that it’s always both about the journey as much as the destination and in case you haven’t noticed because you’ve been busy laying under your sad lamp to find the will to live and spraying the CBD out of you, right now Substack feels like a bumpy ride on a third-class coach (the Bakerloo line for those of you in London) to a no man’s land (that’s Morden for my fellow Londoners) guided by someone who can’t read directions (can anyone these days with smartphones?)

In other words, you wish you could upgrade your means of transportation to a destination of your choice and be in more capable hands.

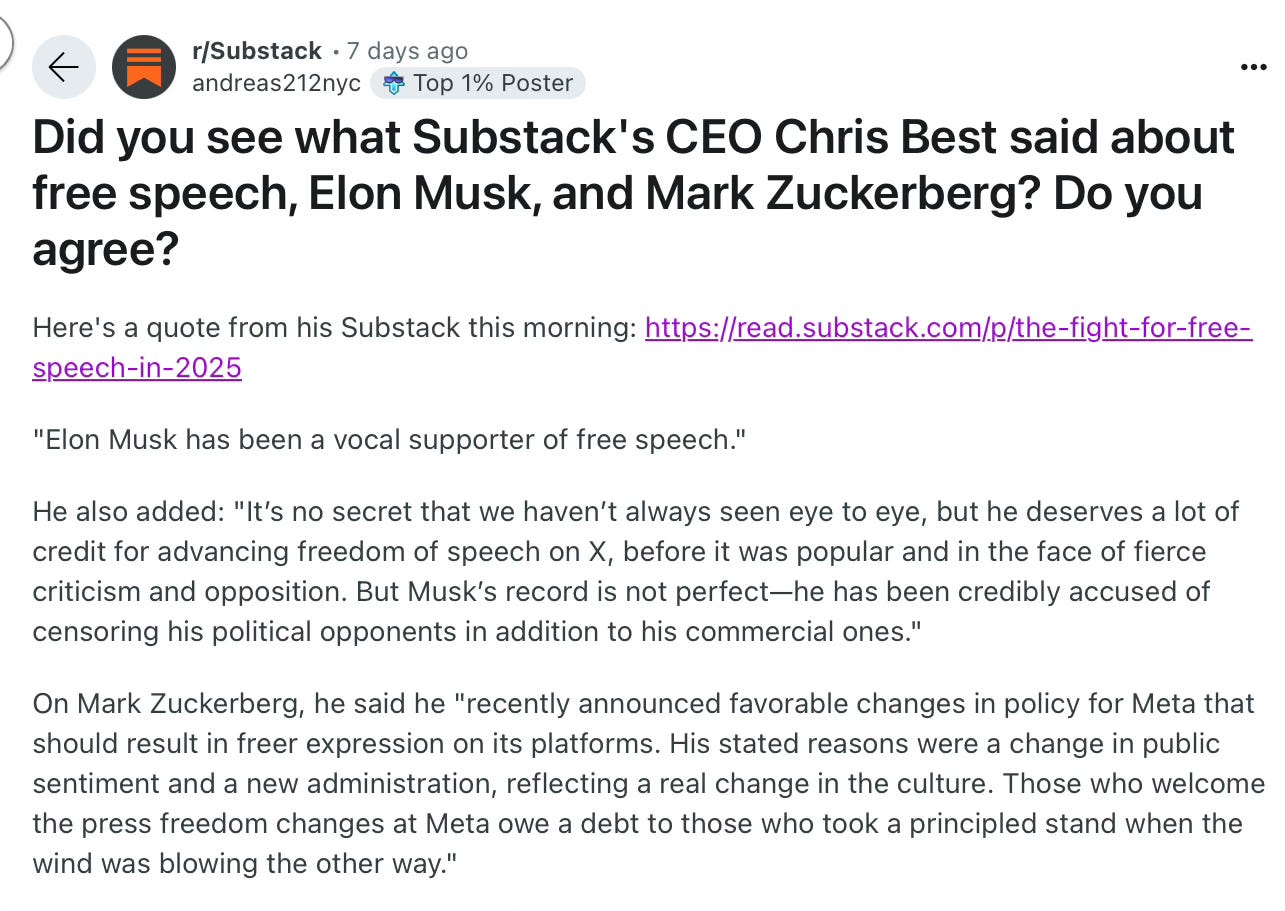

Especially after Substack CEO Christ Best praised Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg as defenders of free speech which a note by brought to my attention.

Wait, are we talking about Substack? The newsletter hosting platform that claims to be an engine for creativity? The same platform where many have found a respite from social media?

And more importantly, are Substack cofounders actually talking about Mark Zuckerberg, the guy from the Cambridge Analytica fiasco? The same Zuckerberg who has announced Meta is throwing fact checkers out of the window to push political content through the revolving door? And the Elon Musk who made advertisers boycott Twitter as harmful content flourished under his rule? The guy who made that salute at Trump’s inauguration?

This doesn’t look particularly promising when it comes to the direction Substack is going into 2025, when a surge of new joiners is expected to land once the TikTok ban comes into force in the US.

If you feel a bit lost about why you should care about this when you are only here because your aunt Margaret has moved to France and started a newsletter about her life there and asked everyone in the family to subscribe so she can share what she bought for dinner at the local marché (look at the colour of those courgettes, dear) allow me to refresh your memory because this is a free speech déjà-vu.

We need to take a few detours, but stay with me and I promise it’ll make sense in the end.

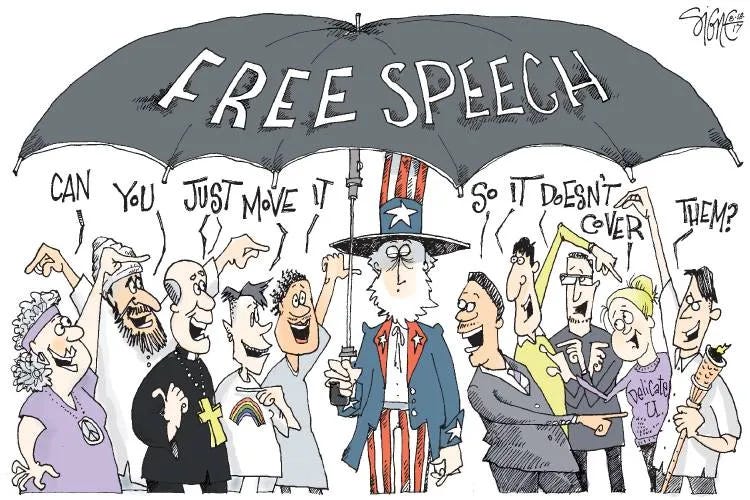

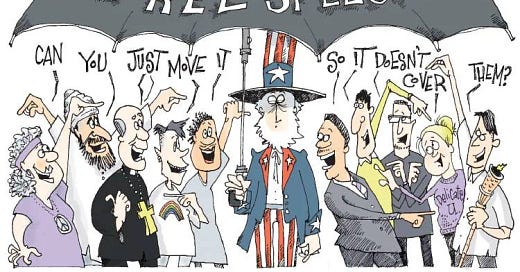

November 2023: Does Substack have a Nazi problem?

In November 2023, when journalist Jonathan M. Katz published his Substack Has a Nazi Problem article in The Atlantic, which flagged a number of pro-Nazi publications on the platform.

In the wake of that article, Substack stated it wouldn’t ban nazi or extremists speech. This reaction seemed taken straight out of Roy Cohn’s rules for winning. If you haven’t watched The Apprentice yet, I can’t recommend it enough. It is beyond timely as Elon Musk seems to have taken a few leaves out of Trump’s (and Cohn’s) book as per Time Magazine’s provocative cover putting Elon Musk behind Trump's desk.

The platform remained firm on their stance even after 247 Substack publications signed an open letter to enquire about why Substack didn’t see a problem in pro-Nazi publications monetising hate speech and why Substack had decided to do nothing about these publications when it is very strict on banning pornography or content that incites to violence. Substack’s refusal to censor pro-Nazi content in the same way didn’t land well and users threatened to quit the platform.

While this may not have made viral waves in the same way the Make Instagram Instagram Again campaign did -arguably because to the best of my knowledge Substack is one of the few Kardhasian-free online spaces left but also because being able to see your friends’ and family’s pictures in your feed first ranks objectively higher in the Kardhasian’s hierarchy of needs-, people did write about what they thought about the Substack Nazigate here, here, here and very eloquently also here and here, where we are reminder this is not the first time Substack has a free vs hate speech problem in its short-lived existence.

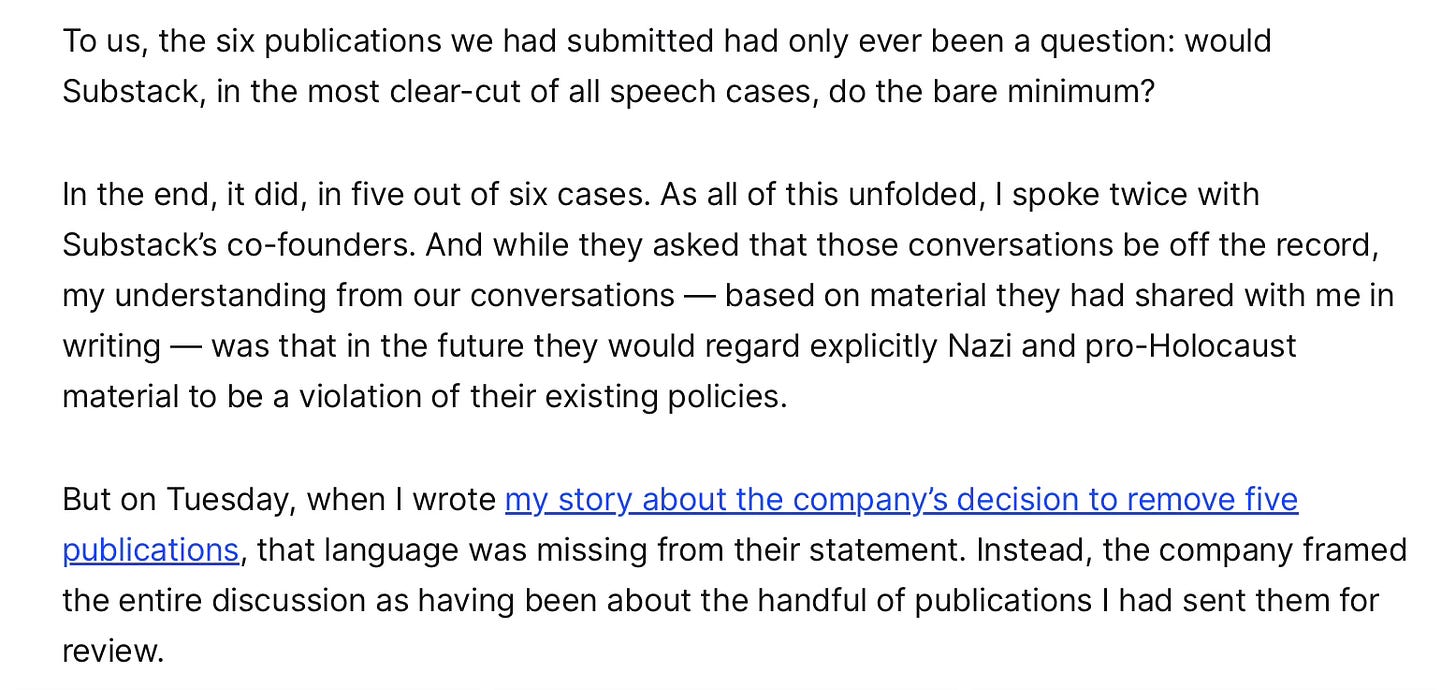

While Substack eventually seemed to backpedal a little by removing five pro-Nazi publications after what for the founders may have seemed a lot of unnecessary nagging, subscribers left all the same.

Among those to jump ship were Jonathan M. Katz himself but also Platformer, a tech newsletter founded by journalist Casey Newton, who took his 170,000 followers to German-based publishing platform Ghost.

In an open later to explain his decision to quit Substack, Newton gives a clear and insightful account of how he came to the conclusion -after much reflecting and conversations with people- that the best course of action for Platformer as a publication, its subscribers and himself as a journalist was to leave Substack.

Notes has joined the chat group (and so have followers)

The question of whether Substack had a Nazi problem became quite topical. And Notes picked up on it spreading it like a wild fire.

Notes is that annoying twitter-like feature released in April 2023 which Substack users can’t opt out from much in the same way they can’t filter which content appears on their feed.

With Substack being a US-based platform the content pushed out through Notes more often than not is heavily biased towards US-centric news and writers discussing said news, whether it’s the US elections or Luigi Mangione.

There’s a reason many people fled Twitter, Instagram and any day now TikTok, as well as traditional news outlets, and flocked to Substack: The platform was a breath of fresh air from the highly divise content and same old stories (many of them favouring a US political agenda already) that are forced down our throat every single day. It felt like a true safe space to get out of the polarising doom gloom that has become so pervarsive in social media.

When Notes was introduced in April 2023 as a new tool it was a subtle but clear sign that Substack was pivoting towards the direction in which many of us had been running away from. No longer a space only for long-form content that requires more focused attention and reflection, but a copycat of the same online noise that was so defeaning.

And while Notes may have been originally introduced with good intentions to help writers connect with each other as well as with a wider audience faster, once the follow button appeared a few months later, it was clear that the newsletter platform was taking a turn towards social media.

With Notes Substack added an embedded social media tool to broadcast short-form content which people can like, comment on without having to subscribe to any publication or the need to read a ful 5,000 words post to have an opinion.

If on top of that you are tech savvy enough, you surely know that controversial content leads to far bigger engagement. And a high engagement rate is the fuel on which viral content feeds off and news, true or not, travel very fast.

Rules for winning in the XXI century: Engage, Engage, Engage

Your aunt Margaret sharing snippets of her quaint life in France, as exciting as it may be for a lot of peole, will never be profitable for Substack because it won’t lead to the inflamed reactions that that infamous guy who keeps writing here about the joys of preying on young girls.

The irony is that people rushing to call out such behaviour on his comment section are fueling his publication to reach out to a wider audience by engaging with it. So you’ll excuse me for not naming him but I won’t contribute to make him more popular and won’t name him. You probably know who I’m talking about by now.

Substack has picked up on as much and with a few exceptions that will be hard to justify (such as pornography or explicit incitation to acts of violence), the platform has a rather laissez faire approach on grounds of free speech. If Roy Cohn’s strategy for winning in the 70s was about attack, attack, attack, in the XXI century is all about engage, engage, engage.

But why engagement is so necessary?

Because you can sell it to advertisers, like Meta discovered back in the day, and translate it into money. But also, and not less important, because it gives you the holy grail everyone is after: Data. Especifically users’ data.

Who reacts to certain content and in which way is the key to understand how to personalise content and what we get to see online across any platform in the hope it can be potentially monetised because it appeals to us.

From your social media feeds or discovery pages to Youtube ads (mine at the moment are about Eastern European women near my area. I’ve had worse), everything you see online is an attempt to get data and money from you. That’s why Instagram didn’t care whether your family and friends pictures got lost among the all the posts from influencers and brands with stuff to sell you.

But Substack doesn’t have adverts or sponsored content, Cristina, I can hear you say.

No, it doesn’t not. At least for now. What it does have is subscribers. 20 million, to be precise, out of which 2 million are paid subscribers.

Substack also has writers earning money from the platform and for many it has become a lifeline in the decline of traditional media and publishing industries, when not their main source of income. And a rather substantial one.

In fact, Substack has provided a tool that allows many writers (consolidated or aspiring) to level the playing field to find their audience by making sharing their writing easy and accessible. It is indeed not necessary to subscribe to Substack to be able to receive updates from your favourite writers as they can be delivered via email.

What does Substack and free speech have to do with Zuckerberg and Musk then?

There is a reason I started this post by telling you, dear reader, that Substack co-founders are elevating Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, long-term fiends, to free speech heroes.

And that in itself can be debated and you may or may not agree with it, but that’s not really the question. The question is why now and why them.

In the second Trump mandate.

With AI on the rise and big names claiming it should be unregulated to avoid hindering innovation and remain competitive and agile against rivals.

With TikTok about to be banned in the US and OpenAI throwing a tantrum because DeepSeek has copied ChatGPT when the reality is that they don’t want anyone else developing powerful AI.

With VC Andreessen Howorowitz stating last November that new rules around regulation on the content used to trained AI models could decrease the value of AI investments if companies have to pay for copyrighted data. The same VC that led Substacks series A and B of investment by the way, something I’ve also written about before.

With more big names in journalism (but also celebrities of all walks of life) joining Substack each day as legacy media is about to expire its last breath and with the expected refugees escaping other social media platforms.

And now let’s take a dive into tech memory lane.

Musk and Zuckerberg have been in a tug of tech war for a while now - I wrote about it back in July 2023 in a former tech newsletter- as the launch of Threads (an opportunistic copycat of Twitter released shortly after Musk took over) pushed Musk to sue Meta for plagiarism but mostly for creating a competitor to Twitter which was already bleeding users, which led Meta to counter-sue.

The whole “you sue me, I sue you” drama escalated quickly and spiralled out of control in the most unexpected way as Musk challenged Zuckerberg to a cage fight. That’s wild, I know, and yet it’s also true and you can read here a detailed account of the events, tweets and all. No, it hasn’t still happened and I’m very disappointed about it. We could have killed two birds with one stone. Metaphorically speaking, of course.

Was it ever about plagiarism? Not really.

It was always about control.

In particular control about the means through which information gets disseminated, how and to whom. Control of the media and, more significantly, of social media is the first step towards making sure you’ll have a devoted audience (and their valued data) when the time is right to get your message across.

And here we need to take another quick step back to put things into bigger perspective.

For years Meta (then known as Facebook) dominated social media landscape without relevant competitors - at least until the arrival of Instagram, which Facebook bought for 1 $billion to make sure it wouldn’t become a rival. For a number of years, Facebook and Twitter were on friendly terms but when the latter started to grown, Facebook didn’t allow Twitter links to be displayed on its platform, which impacted Twitter traffic1.

Facebook had undisputed dominance and with that came both opportunities but also the problems because it is a truth universally acknowledged that with great power comes great data responsibility.

No one must have been a fan of Spiderman at Facebook HQ because otherwise the Cambridge Analytica scandal could have been avoided and with it the pains is still causing to Facebook Meta. But it didn’t take Cambridge Analytica to get personal data from Facebook user’s without their knowledge as there is evidence Facebook had been doing so from as early as 2011.

Fast forward to 2021 when Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen revealed the company’s behind-the-scenes unchanged practices and how their access to users’ data was harmful for its younger users as well as for democracy as the platform knowingly pushed content that generated greater engagement, which came in the form of highly polarising opinions, which translated into a bigger profit via advertising space.

Shortly after Haugen’s revelations, Facebook announced a rebranding. Zuckerberg’s ambitions to dominate the metaverse (which failed by the way) may have had a lot to do with it, but no doubt the whole process was speed up after Facebook’s image was publicly tarnished again after the Cambridge Analytica scandal and for very similar reasons.

Meta was born but as we all know the habit doesn’t make the monk. Musk did the same rebranding trick with Twitter (and previously with himself) but I refuse to name it for its current ridiculous name so I’ll only say that it got blocked in some countries as it had some porn connotations. And if you’re also interested in the personal Zuckerberg, Musk and alt. rebrand to the right, I recommend reading We’re ruled by Losers, a great piece by

Make access to users’ data great again (and push your agenda as you please)

There is no coincidence everyone who is someone in big tech was at Trump’s inauguration.

Especially when he has announced aggressive AI plan for the US, “free from ideological bias.” What is code for free from regulation, because in the age of artificial intelligence, access to data is the holy grail. There’s a reason software engineers -the rockstars of tech for many years- are retraining as data engineers.

The US Government’s rationale for banning the use of TikTok or concerns over DeepSeek use of users’ data is in reality about making sure no outsiders can get a piece of the big American “AI development and access to users’ data” pie.

Because if we put all the pieces together, there is a clear narrative taking form: The need for US tech leaders and platforms to come together as one to control the means through which information gets disseminated (and freedom of speech is the name of the game so you can push anything) and to whom (for which you need unregulated access to users’ personal data so your AI algorithm can be effective).

And this better be done by good Americans like Zuckerberg, Musk, Jeff Bezos or Sam Altman who want nothing but to defend their freedoms against outsiders. Especially if they want to remain billionaires.

However, a Zeyneck Tufecki has argued in an recent opinion piece on the NY Times:

The misguided focus on containment is a belated echo of the nuclear age, when the United States and others limited the spread of atomic bombs by restricting access to enriched uranium, by keeping an eye on what certain scientists were doing and by sending inspectors into labs and military bases. Those measures, backed up by the occasional show of force, had a clear effect. The world hasn’t blown up — yet.

But how is Substack going to monetise the US government’s anti-regulation approach on all things AI and the free speech discourse under which nothing gets censored in the name of profit, I hear you ask.

Unlike Meta platforms and Twitter, Substack it is currently ad-free, but it takes a 10% cut on paid publications. However, it is still not profitable.

But contrary to Meta or Twitter, which don’t allow the visualization of their content if not registered first, Substack’s model has found a way to get content to people without them even needing to sign up to the platform or be on it.

And with 20 million subscribers, there is potential for pushing forward controversial writers or content on grounds of free speech to increase their visibility and potentially attract new subscribers to join the platform or pay for content, increasing both the writers’ and Substack’s revenue.

It may not be as straight-forward as plain advertising or sponsored content, but it is a tried and tested strategy to win online audience’s attention and drive engagement: Divide and conquer.

The more controversial the content (because you are a free speech defender), the higher the engagement and the bigger the profit. Therefore it is not less significant that Substack cofounders have been looking up to Zuckerberg as their free speech guru.

And when the government regulators are on your side, sky is the limit.

A note on the European approach to free speech and regulation

Trump’s agenda on AI -and its profit over safety approach- is in clear contrast with the stance the European Union has taken on AI through the enforcement of the EU AI Act to provide a legal framework for the development and uses of the technology, but also to safeguard users and prioritise their privacy and safety.

As Stephen Bush said in a piece on the Financial Times about the response Substack offered about its free speech versus pro-Nazi problem:

Of course, there are other ways that British and European law is a colder home to free speech than the US. But as we contemplate the lessons from this Substack spat, one of them is that in an era in which more and more communication is facilitated by private providers, broad European-style protections for political views are a model worth copying […] If Substack were a European or British company, the matter would not even arise: both the European Convention’s Article 11, on freedom of association, and even more explicitly the UK’s 2010 Equality Act, place sharp limitations on the ability of businesses or states to discriminate on the grounds of politics.

Under a new Trump administration which has revoked President Biden’s executive order on addressing AI risks, it is significant that the first thing Meta has done is to openly talk about how they’re removing fat-checkers to restore “free speech” and pushing more political messaging is clear where everything is leading to.

With the upcoming Artificial Intelligence Action Summit taking place in Paris next week and the European regulators recently discussing which AI tools will be removed shortly as considered too dangerous, Sam Altman hasn’t missed a beat and, ahead of his participation in the summit, he’s repeated his usual take on how too much regulation could hold Europe back in the AI race.

He is an interested part as OpenAI announced the opening of their London office back in 2023. A clever move as the UK is no longer part of the EU, and the regulations adopted by Europe do not immediately apply in the UK. However, British companies with a presence in Europe do have to comply with regulations on the continent.

Around the same time OpenAI announced its London launch, the UK government’s vision on AI and potential regulation was set out on the white paper ‘A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation.’ In January 2025, PM Keir Starmer unveiled a new AI plan to turbo-charge growth and boost living standards. However, British citizens seem to want stricter rules than the government does.

Perhaps that’s why the UK PM won’t be attending the AI Summit in Paris next week.

The official version is that he’s focusing on his domestic agenda as he’s received previous backlash in the past “for taking too many foreign trips.” You’re telling me the Prime Minister can’t go to Paris to discuss what the UK government plans to do on AI when the US is on a wild anti-regulation ride because people may complain he travels too much? Seriously?

Time will tell how the UK’s Prime Minister’s absence impacts conversations but something smells fishy here.

OK, but how do EU regulations impact Substack?

If Substack incorporated anywhere outside the US, more particularly in Europe, they’d be subject to EU regulations. If the company had a base in the UK from which they offered their services to mainland Europe, they would have to comply with stricter regulations.

And with the Digital Service’s Act regulating online platforms or specific measures to address freedom of speech online, something the EU really loves is to regulate. As Meta has learned the hard way. So did Musk when Twitter’s algorithm came under the attention of French regulators.

The other thing is that they would also be subject to paying taxes on the territories they’re in. Who would willingly want to do that when they still have to make a profit?

As the saying goes: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

In fact, Substack has come up with a win-win business model: The company pays zero taxes outside of the US while operating globally and it leaves users (at least in the UK) to deal with the mess of calculating taxes for subscriptions received anywhere in the world via their payment service, and takes a 10% cut for the work someone puts into avoiding committing fiscal fraud over pennies.

If that’s not enough it has also managed to build it’s own integrated social media platform while also delivering emails so content travel faster to anyone, whether they are subscribers or not. All this while making free speech great again and promising to be an engine for the creative economy.

Netflix could do four new seasons of Call My Agent retaining it’s original French title, not for nothing called Dix Pour Cent, based on the Substack business model alone. Instead of actors, we would have amateur writers complaining about how much tax they have to pay in Denmark versus Argentina for a subscriber based in Kuala Lumpur and another in Lagos. I think it has potential to become a global hit.

So what does this all mean and why should we care?

The easy answer is because if you’re reading this, you know what Substack is and therefore I am of the opinion that it should matter to you to know how the platform works beyond its features for writers.

We’ve learned that Substack makes money from anyone with a paid publication here. We also know that controversial content is much more likely to prompt people to react which drives engagement and that in turn leads to bigger potential for monetisation.

The more elaborated answer is that Substack cofounders’ nod of approval to two controversial tech bros -who have not only not given us the cage fight we were promised, but are done nothing to regulate harmful content in their platforms or protect users’ privacy in name of profit- as free speech heroes is very revealing of the direction of travel the platform may take in the not so distant future under a new Trump administration favouring profit over users’ safety and privacy in the race to build the AI of the future.

If push comes to shove, we all will have to think very seriously about our individual engagement with a platform where anything goes. The good, the bad and the ugly.

This in itself may become another highly polarising topic among Substack users and subscribers, who may end up pointing fingers at each other to know where they stand. This can be a bit of a shit show and not solve much.

Many writers swear by the freedom Substack has given them, and how they can make a decent living thanks to having control of their writing and a closer relationship with their readers. Now imagine what would happen if readers started to question those writers for publishing here, which could be viewed as an act of indifference or even veiled support to the ‘anything goes’ view when it comes to the kind of questionable content the platform allows in the name of free speech as long as they aren’t proactively engaging with it or producing it.

This of course a very simplistic hypothesis of how events may unfold in a worse-case scenario.

If you’re a writer earning a living thanks to Substack, this is a very complex and much more nuanced argument. If someone has struggled to break out into traditional publishing and have found an audience and a means to financially support themselves here, quitting may not be on top of their mind nor the most desirable outcome. We all have to eat and pay bills at the end of the day and we may not always have an alternative place to go or source of income.

On a more prosaic level, Substack may also be a place many of us enjoy because it has allowed us to explore a passion that brings us joy and connect with people we genuinely like interacting with. We have found exciting writing and food for thought that was unavailable anywhere elsewhere online. Why should we give up a good thing when we aren’t personally supporting the hate speech spreaders nor engaging with them?

Or aren’t we?

The reality is that a part of what we pay for reading writers here- the good, inspiring, and decent ones as well as the controversial and divise- and of what you get paid by your readers (of any walk of life and ideology but pecunia non olet), goes to the pockets of people who are fine with hate speech being not only published but monetised on Substack.

This could create a moral conundrum because as much as we can enjoy the many positive aspects of this platform, Substack is a business and its ultimate goal is to make money.

Although we can also argue that it is possible to make money while preserving free speech by regulating harmful content firmly and openly. In the new Trump administration that wouldn’t be happening anytime soon, I’m afraid, because it would make a dent on profit.

Final thoughts

I hope I’m proven wrong in all of my hypothesis regarding the future of Substack and that it remains as it is for as long as possible. It isn’t perfect nor the blissful online oasis one would may wish but it’s not a pit of online despair either.

However, I’m a bit skeptical.

The arrival of Notes, podcasting, voice and video features (as well as the AI tracking button that I hope you have turned off in your Substack) are indicative of how the platform has already pivoted to cater to and attract users who prefer any of those mediums over long-form writing.

The vibe shift as more social features and big names have populated the platform has been obvious for a while now.

Substack is becoming something else, still undefined and in incubation, but no longer just a space for writers that want nothing more but a quiet place to share ideas and without the dynamics of social media, or the constant push of someone’s political agenda on their feeds to influence their thinking and opinion. Unless I’m mistaken, that’s what we may see more often happening here via the content and writers that get pushed on the platform by the platform.

If we get to that point, dear readers, I hope we can make Substack great again. At my signal, unleah hell. Always metaphorically speaking because we all know our weapons will be the keyboard, capital letters (in bold if really provoked) and profuse exclamations marks.

Although that could also be a good battle cry to invoke that cage fight between Musk and Zuckerberg. I haven’t still lost hope it’ll happen in my lifetime.

Abroad is an independent publication about London, living in between cultures, languages, books, music, films, creativity, and being human in the age of artificial intelligence.

If you enjoyed this post, like, comment and share as much as you like as that will help me inflict my thoughts on a greater number of people, which has been a childhood dream of mine. And if you find yourself here regularly, consider subscribing to receive updates and support my writing.

To understand the power dynamics of US-based social media platforms, their audience wars, and why TikTok has become such a threat for them, I strongly recommend reading the excellent No Filter by Sarah Frier. Although it focuses on the rise and evolution of Instagram, the picture-sharing platform’s history is intertwined with the nascent social media scene and the birth of Silicon Valley and how each of the emerging apps and platforms searched to attract their audience but also understood the importance of collaboration, even when it simply meant tolerating each other, or the need to wipe out competitors (Facebook’s preferred tactic).

Thanks, Cristina.

Modern life really is rubbish…

And there’s no escaping the algorithms for any of us now. Of that, I’m absolutely certain.

Thanks for that run down Cristina. To paraphrase a rom-com 'We're just writers, looking at a platform, asking it to stay morally sound'...2025 is panning out to be exhausting. I think I need to find a cave.