Bloody pussy

Someone fainted during a key moment in the stage adaptation of Annie Ernaux's The Years. I can't stop thinking about it and what it means.

Who would have thought Upper Street would be so busy on a Saturday afternoon?

Move, move, move! Out of the way! Bloody hell, what’s happening today??? Fuuuuuck! Sorry, sorry! Yeah, well, sorry again! (Coglione) Oh shit! Mannaggia a te!

I’m darting across the street to make it to the theatre on time for the play I’m coming to see and in time to drink the boiling coffee on my right hand, or what’s left of it after having spilled half as a result of bumping into a distracted pedestrian who was absorbed in his phone and unable to move out of my way like any decent person would have done when he saw me charging against him. Instead, he is expecting me to apologise profusely for his lack of attention when my coffee is lying all over the pavement, the innocent victim of an easily avoidable collision.

I am not in the wrong so I ignore whatever he keeps saying to me in the distance. I only have 13 minutes to get to the theatre, drink my coffee, eat my muffin, go to the toilet, and find my seat. I keep running while swearing in Italian out loud, in part to insult the man responsible for my coffee gate and in part because it’s a default setting when I’m late, and I only stop -running and insulting- when I reach the theatre a few minutes later. I thought I was in a worse shape but look at me: sprinting and talking at the same time without losing my breath. If this was an Olympic sport, I could have easily got a silver medal. Gold with a bit of training. It’s been a while since I’ve last insulted people in Italian for so long and I’m a bit out of practice.

Outstanding performances aside, I’m finally outside the Almeida Theatre, in Angel, where I’ve come to see a stage adaptation of Annie Ernaux’s memoir The Years.

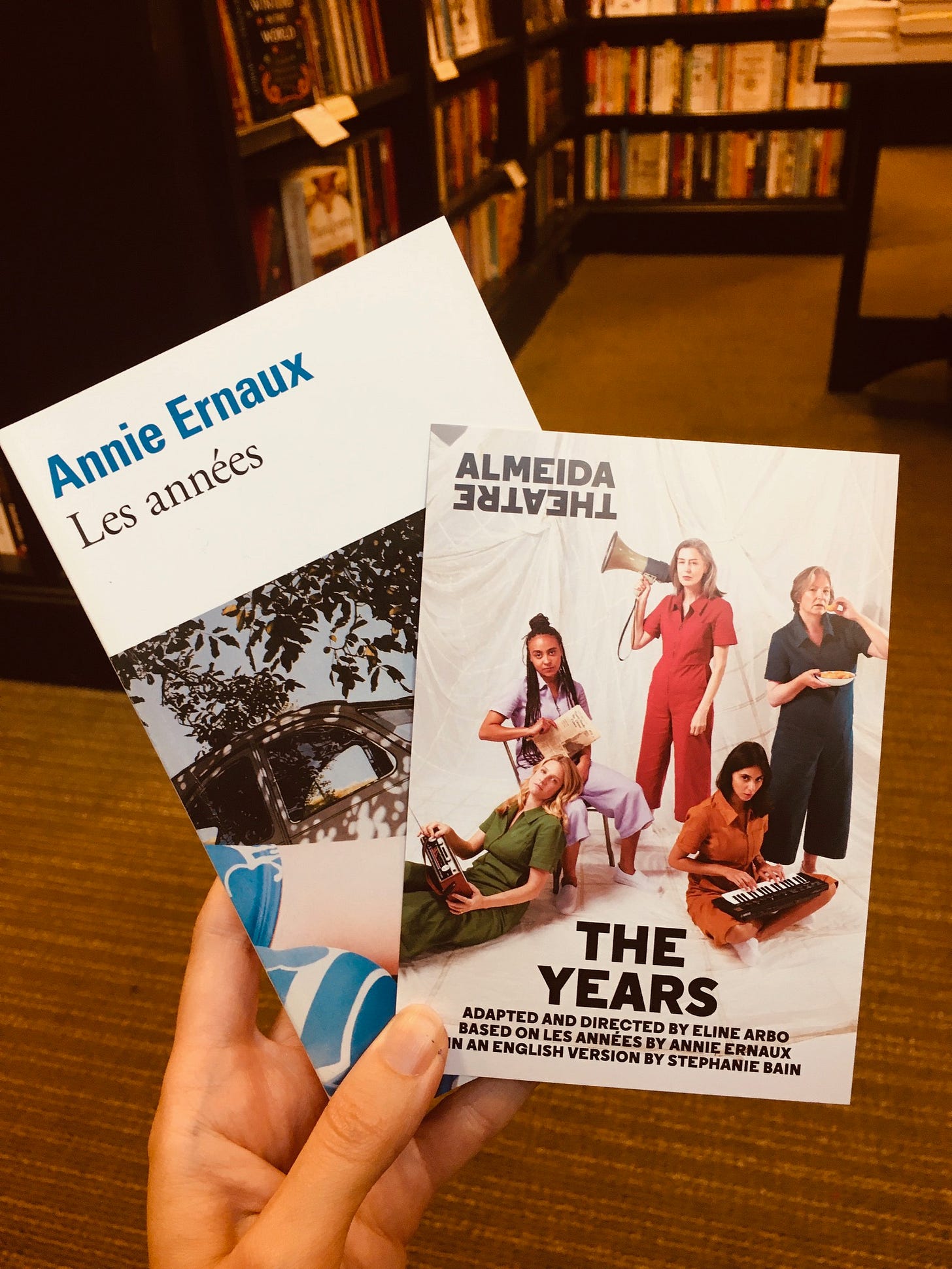

While I haven’t yet read the book (mea culpa), years of French classes have made Ernaux and her work a familiar name in my literary vocabulary.

Les Années, in the French original, is an encompassing personal as well as historical account of post WWII France, and I’m very intrigued to see how it translates from the pages to the stage. This adaptation seems a great introduction to Ernaux’s text and the push I need to finally read my copy of the book, which is somewhere among the Folio paperbacks that are piled up in the French section of my bookcase.

As I take my seat, I discover with delight that I am quite close to the stage as the Almeida Theatre is a cosy venue. I’m thrilled as I’d be able to see from up close Romola Garai, who I’ve recently seen in The Hour where she was fantastic. A review of the play that I’ve read this morning informs me that Garai is responsible for performing one of the key scenes, an abortion, which apparently has caused quite a stir among members of the audience, mostly men.

I’ve learned to take these headlines with a pinch of salt as they don’t always reflect the general audience experience, but more a particular incident on a given day.

Years ago there was outrage at a new production of William Tell at the Royal Opera House as the audience booed during a rape scene. I thought it would have to be quite crude to provoke such a reaction as the Royal Opera House crowd is rather seasoned and unbothered by anything, at least in my experience of regularly attending performances for the past 15 years. I wasn’t wrong. When the rape scene came no one batted an eyelid. The scene lasted less than a minute and it made sense in the context of the action and the increasing tensions among the characters. Before I had time to be outraged, it was over. No one booed and judging by the length of the applause at the end I’d go as far as to say people had a good time.

That’s not to say there haven’t been moments where I have been shocked when others saw no reason to lift an eyebrow.

I remember a production of Don Giovanni where characters in advanced stages of semi-nakedness engaged in sexual acts throughout the performance that looked, in my expert opinion, a bit too realistic. I’m no prude, but I promise you it wasn’t clear it was all acting. However, my seat neighbour, a lady in her 70s, exclaimed quite neutrally after a confusing scene, “Oh, well, I guess it was to be expected” to which her female companion, also in her 70s, responded, “He was a bit of a libertine it seems.” And that was it.

Were they talking about Mozart or Don Giovanni? I could never tell as they felt no need to elaborate further on this live, amateur Pornhub-worthy, 3 hour-long performance. I honestly have the utmost admiration for the capacity of older generations to be immune to what younger generations often find outrageous. You have to agree that not being constantly on your guard monitoring when to feel shocked or offended it’s quite liberating.

As much as I wanted to go into The Years with as little information as possible -considering I know what it is about- it wasn’t meant to be. Before reading the review I had received two emails from the theatre detailing all the trigger warnings for this play. So in addition to potential fainters I knew there would be blood.

I find it amusing that while there is a tacit understanding that theatre is all pretence, we also look at it as a mirror to life, perhaps the closest artistic representation of it. And yet, I am being reminded, not one but twice, of how fake everything that I’ll be seeing on stage later on today is so that I am not shocked when it happens and, fingers crossed, manage not to faint. It’s as if someone had decided that to minimise the risk it’s important to stress I am paying money for something that isn’t real. I would have understood this level of insistence if I had bought an NFT, but it feels a tad excessive for a ticket for a play.

The list of all the actions that will be totally bogus, completely made up, fake as the promises of a politician during election period include:

A graphic depiction of abortion

Blood

A coerced sexual encounter

Sexual content

In addition to the above, there’ll be also smoking of e-cigarettes, haze and flashing lights.

The mention of e-cigarettes is quite interesting. Who actually cares about e-cigarettes? I imagine only a sociopath that, going through each item, nodding reluctantly in approval, finally explodes in rage, “Oh no, not e-cigarettes too!”

I understand that trigger warnings are a welcome -sometimes even expected- addition these days, especially when members of the audience may have been through some of the events that will be enacted on stage. It wouldn’t be the first time that a recent play adaptation causes people to faint or leave the theatre in distress.

However, sometimes it feels as if the general public had undergone a process of infantilisation. The amount of whining about the tiniest detail that can potentially upset a person in a play1 , movie, book, song, message, article, tweet, social media post or serving suggestion (“How dare you not made it obvious that my cereals would not come out from the box with fresh strawberries and yogurt!”) is absurd.

My perception is that this is more of a phenomenon in Anglophone countries, where often there’s a heightened sensitivity for these matters and a better customer service. In Southern Europe trigger warnings are called “deal with it.” I’m not saying it’s a better method, but it certainly prepares you from an early age for the uncertainty of life and the punches it’ll throw at you without warning.

Would I have liked someone to tell me in my teens that I was about to read a story where this guy crosses paths with his father, but doesn’t know who he is, and then years later he kills him, ends up shagging his wife, who happens to be her mother, and when he realises what has happened, he blinds himself before going into exile? Or this other story about this woman that is abandoned by her cheating husband and goes on a killing frenzy murdering his new wife as well as hew own sons before starting a new life in Athens?

Maybe, but Sophocles and Euripides would have been less of a page-turner and sometimes you need a shocking plot twist to keep you on your toes. The Greeks invented drama. They knew what they were doing and how manipulating a loving son to turn him into a kidnapper, and the cause of the downfall of Troy, probably in revenge for his parents’ attempt to murder him as an infant, could be the basis for a compelling narrative that can transcend the test of time and any imaginable trigger warning.

Despite the insistence in making me understand that I am about to see a fake representation of events, I am still hoping to be surprised, wowed and transported from the reality of the four walls of this setting and into the changing landscape of the France of the youth, adulthood and maturity of Annie Ernaux.

People making their way to their seats are all holding drinks. If only someone would have bothered adding to the list of trigger warnings that in the UK you can bring your drink into the theatre -something I always forget as it’s completely alien to me- I could have spared my oesophagus and larynx an express abrasion as I gulped down what was left of the coffee outside the theatre.

I also notice that most of the audience today is north of their 60s and 70s, with only a few of us slightly reducing the average age in the room. That probably explains why most of the people are drinking alcohol at a matinée performance and holding two glasses as there is no break. The audience in this play belongs to a generation that sends down drinks with the same determination Millenials clock in their 10,000 daily steps. They can’t afford to rest if they want to hit their weekly alcohol units target.

As the lights go out and the audience goes quiet, I wonder what has attracted these people to a play so distinctively French and covering such personal experiences in the life of a woman. Would there be any fainters today and if so, who would they be? My money is on the tipsy septuagenarians holding gigantic drinks. After all today we speak quite freely about many subjects that in the past have been deemed taboo, whether it’s periods, abortion, sex, contraception or women’s rights but back in the day it was all hush hush. This performance may be a bit too much for those of a certain age. They realities of being a woman, and the intoxication, is about to hit them in the face.

Fifteen minutes in and the play is phenomenal.

I am totally captivated by the clever production and in awe of the five actresses playing interwoven memories and different versions of Ernaux across the decades. Gina McKee and Deborah Findlay during in her mature years; Anjli Mohindra and Harmony Rose-Bremner, in her youth; Romola Garai during her transition into adulthood, which is one of the most transformative periods in Ernaux’s life as she goes from having a back street abortion in 1963 to becoming a mother shortly afterwards.

This is the moment indeed all the trigger warnings have been preparing audiences for.

Romola Garai is now all contained emotion and mixed feelings on stage, her voice carrying the shock of discovering her unplanned pregnancy as a single, young woman at a time in her life when she had finally got a taste of a future she had longed for. The only solution is to have an abortion. An illegal one that is, as the practice was only decriminalised in 1975 with the Veil Act, promoted by Simone Veil -another force of nature- during her time as Health Secretary of Estate. Ernaux described the traumatic experience of her abortion in L’évenement (Happening), which was adapted into a film in 2021.

Something about the raw performance of Garai on stage makes you hold your breath as you feel everything Ernaux must have felt in that moment.

The fear of being pregnant, the fear of ending up in jail if caught having an illegal abortion, the fear of dying in the process. And then everything reaches the climax we feared. After having visited a nurse on a back street who has unceremoniously worked on her body, the contractions start at home the following day, and Garai twists and turns on top of a table, giving her back to the audience.

When she finally faces us, we see blood running through her thighs. Fake blood, that is. All goes smoothly because we have received enough trigger warnings by now and also because this is, after all, a play and we all know Garai is not really going through this experience.

As she delivers a monologue during which you can hear a pin drop, I am ecstatic watching her mastery of the stage and command of the audience, which is captivated.

And then it happens.

“Oh dear. Are you feeling alright?”

The voice comes from a few rows back from where I am seated. Not loud but not a whisper.

“Are you ok? Talk to me, please!”

There’s an urgency now in the tone, the voice slightly louder. I hope it is not what I think it is. Not now. Let Romola finish, have some respect.

“Excuse me, can someone please help me?”

It’s official. Someone has fainted.

A member of staff goes onto the stage and the lights come up as there’s a growing rustling of voices in the room. Romola has remained silent, probably aware of what’s going on at the back and what it means. Another play, another faint.

“I’m very sorry for this interruption,” says a woman on the stage with short blond hair, dressed in black and carrying a clipboard and a headset, “but a member of the audience is feeling unwell and we have to stop the play to allow them to leave the theatre.” She is neither too apologetic nor worried. Like Romola she has dealt with this before. “Thank you for your understanding. We’ll be resuming the performance shortly.”

You may be wondering who that person was.

I would like to say that I don’t know because I respected their privacy in such a moment of need. After all it could have happened to anyone. But the advantage of being a highly judgemental person full of contempt is that I’m beyond moral salvation and therefore there’s no need to pretend I understand. Especially when someone has ruined the most cathartic experience of my life for failing to handle what clearly is a bit of coloured water. So as soon as the lady on stage disappeared I turned around to identify the culprit.

A man.

Reader, I cursed him.

From what I can see from his physical appearance as he heads towards the exit he seems to be in his late 30s, early 40s.

Isn’t this someone in theory more in sync with the times? #Metoo, #timesup, #mybodymyrules, #couplegoals, #veganuary and all that? Yes, I know #notallmen but clearly #thisman.

A man followed closely by a woman, who I suspect was the owner of the voice that broke the silence moments before asking for help.

A woman for whom the play has also been ruined despite not being the one feeling disturbed by the sight of fake blood when she has the real deal conveniently delivered to her cervix doorstep every month.

A man who is dating/living with/married to the woman who has taken him out of the theatre and who, I presume, bleeds every month. I hope she gives him a trigger warning to avoid any further shocks, “Period incoming, I repeat, period incoming!”

A man that I want to believe hasn’t been to the theatre for the first time today and who has received the same two emails I have been sent with the same trigger warnings mentioning there’ll be blood and an abortion. Both fake because this is a play.

A man who previously to this experience is fair to assume has watched violent and crude scenes in movies without fainting or otherwise he wouldn’t be in a play with these trigger warnings.

A man that didn’t seem to experience any discomfort earlier on, during the two scenes that depicted a sexual assault and which were more uncomfortable to watch as they portrayed an act of violence against a woman.

A man who also produces bodily fluids and who has probably never flinched when seeing them smeared all over the body of a woman, whether in real life or in porn, because it’s a natural thing, and there’s no reason to be so squeamish but who I bet finds period sex disgusting.

A man, like all men, who has never dealt with the shock of finding blood, real blood, in your underwear for the first time, not knowing what it’s happening to you.

A man who doesn’t know the fear of not discovering blood in your underwear when you are expecting it impatiently, counting the days it’s been missing.

A man who has never been embarrassed by the unexpected arrival of blood and has never worried about who to ask for emergency pads or tampons in a room full of mostly men.

A man who will never understand the contradictions of wishing your period to disappear for good while fearing the day it eventually does.

A man who has never found itself experiencing excruciating pain when the blood arrives, feeling his organs being ripped apart, and needing to be taken to the A&E for an injection to manage the cramps that are twisting the body in two.

A man who has never needed to make up an excuse to miss work due to having his period and feeling like shit while knowing he cannot say the real reason he is feeling like shit and has to stay at home is because he has his period. It wouldn’t look professional; someone could always accuse him of making it up or use it against him.

A man who not even once has had a holiday he’s been looking forward to, or any special occasion, ruined despite the careful planning months in advance to make sure that specific moment wouldn’t be ruined.

A man who doesn’t need to take a questionable mix of chemicals designed to wreak havoc on his hormonal system, causing him headaches, mood changes, bloating or nausea, to prevent a baby bump.

A man that all women present in the room, especially those who have given birth, are silently feeling sorry for, as a thought crosses their mind, “That’s nothing. You should have seen the things that have come out of my vagina!”

I’ve always thought, and this situation only confirms it, that the world would be such a different place if men had periods, were scared of getting pregnant and gave birth.

Instead we have to deal with this: A man that the audience wishes he could hurry up so we can go back to pretending the coloured water leaking from Romola Garai’s thighs -which she has put there herself when she had her back turned to us- is actually blood.

A man, in short, that despite not being deserving of such high honour, is nothing but a bloody pussy.

As the play resumes, Romola Garai goes the extra mile to bring the audience back to the collective cathartic experience we were immersed in before the BPI (Bloody Pussy Incident).

It takes me a few minutes to reset but once I tune back into Garai’s mesmerising performance, nothing else matters, only the events that transform France and Ernaux’s life during the decades.

And with them along comes the transformation of the young adult played by Romola Garai into the mature Ernaux, played by Gina McKee, as key milestones succeed one another with every passing year: the arrival of the contraceptive pill, the relocation closer to Paris, the disappointment with married and bourgeoise life, the end of the war in Algeria, May 68, divorce, the end of the Vietnam war, sexual freedom and lovers (some older some younger, all equally fascinating to her), the emancipation of women, the arrival of capitalism in the 80s, the heartbreak, the dreaded effect 2000, the life of a woman beyond motherhood.

There is an in crescendo in poignancy as we approach a more mature version of Ernaux, played by Deborah Findley, where the passing of time and the realisation of being the last link of a future once imagined and now mostly dissolved into a recent past takes centre stage.

Would our life had been better had we been born in a time full of freedoms, like our children? Or would we have wasted it away, taking for granted the delay of adulthood and with it the responsibilities thrown into us at a young age and who made us who we have become? Would we have made different choices?

When the lights go out there is an explosion of applause in the room, followed by a standing ovation. I’ve never seen anything like this before nor felt the need to clap with such fervour while springing from my seat in unison with a group of strangers. Good thing BP left early. He couldn’t have managed in his state.

Once the applause dies down and the lights are turned back on someone behind me exclaims, “That was quite extraordinary!”

A man. An old man.

No doubt one of the septuagenarians who were carrying a drink in each hand two hours ago and who has managed the abortion scene in the same way my Don Giovanni neighbours handled the nudity and ‘simulated’ acts of fornication: Impassibly.

And yet it is clear he is not indifferent to what we have just witnessed. There is a refreshing appreciation in his tone that I would have not expected from someone his sex and age.

“Did you enjoy it?”

A woman, in a similar age range judging by her voice. His partner, a friend, perhaps a relative?

“Absolutely. It was very clever, too.” A pause. “Pity that fella had to be taken out.” Another pause in memory of the fallen. “But the actress managed to get back on track quite well, I think.”

“Oh, she’s very good, isn’t she? I’m glad you had a good time.”

Her voice is soothing, but the tone is a bit dull, a sharp contrast to his chirpy enthusiasm. They must be friends, or siblings.

“I adored it. Wish I could see it again.” Another pause, as considerate as the previous ones. “Maybe without anyone feeling unwell.”

“Yes, that was unfortunate. I’ve heard it’s happened a few times.”

“I wonder what it is that makes the poor fellas go jiggly like that. Do you think is the blood?”

His question is exempt from any judgement, and carries the genuine curiosity one would expect from a child. I wish I could turn around discreetly and have a good look at him but it’d be obvious I’ve been eavesdropping. I hear him stand, ready to leave. I let him and his companion make their way out in anonymity but as she follows him on their way out, I manage to catch her answer, “How could I tell, dear?”

There’s mischief in her words, followed by giggling from both of them. Definitely not siblings.

While I will never know who this man is (nor his lucky companion), I can safely say one thing about him: He’s certainly seen his share of bloody pussies. And it shows.

Abroad is an independent publication about identity and belonging, living in between cultures and languages, the love of books, music, films, creativity, life in London, and being human in the age of artificial intelligence.

The four hours of A Little Life stage adaptation is something no one should have endured. As it’s the reading (and writing!) of a novel that is emotional porn for Gen Z. There, I said it.

If it’s half as good as the play, we’re in for a treat

This takes me right back to my London theater-going days and also just made me laugh at loud several times. But it's also truly thought-provoking and has inspired me to read The Years. Thank you for the great essay.