The Cost of Living

A London drama in three acts exploring material safety, the real cost of culture and how the 15-minute city is a reality the rich already live in even if not by that name.

ACT I

September 2009

A young and ambitious me unwillingly arrived in London for what I thought would be a three-month stint to do an internship in order to finish my Master’s degree in International Relations.

I had been to London only once before. To be precise in 2007 with an ex-boyfriend to visit friends of his who lived in a shady studio full of humidity in Shepher’s Bush. The only reason I came was to visit the British Museum and the Sherlock Holmes Museum, which I loved, but the city was nothing I was impressed by and in fact I hoped I never had to come back ever again in my life. It was dirty, expensive and gloomy.

In a joke of destiny I was sent to London for my internship, so that went well.

As weeks went by, I started to like the people I was working with and became more confident in the tasks I was assigned. London remained hugely unexplored as I had a 45 minute commute and I lived in a less than desirable area where, for the first time in my life, I was afraid to come back to after dusk.

This was not only a perception, but a reality. In the first three months someone tried to rob me on the bus back home, a group of teenagers assaulted me in daylight (I feared the worse) and the local thugs found it funny to send their enraged pitbulls against me every time I had to cross where they were, which happened to be in the middle of the only way I could get back home.

My flatmates, on the other hand, were all nice and quiet. So inside the house things were great, the problem was outside those four walls. In a way I feel that experienced already prepared me for the pandemic as I spent most weekends in the flat to avoid going over the same harrowing experiences I had to confront every day in order to go to work.

I had never wanted to leave a place so badly, but back then I had little to no money, I had to complete this bloody internship and I needed to pay for the rent (£320 for a teeny tiny room but with all bills included), transport and food with the peanuts I was given as an intern (£400) so I ended up living with 5 other people in a sub-sub-let council flat in an area where I feared to walk along and where besides a daily dose of misery and decay I had access to nothing else.

April 2010

I was offered a permanent position at the place I was doing my internship. “It’s not a lot of money, but we really like you and we’d love you to stay” the director of the place told me. Salary was indeed a bit on the low side by London standards but it was definitely an improvement from living on £400 a month and I could envision leaving the dreadful area I was living in. A bit of light at the end of the London renting tunnel.

My then boyfriend relocated to London following the news of my job contract. He was finishing an internship at a think tank in Brussels which happened to have their main office in London, so he was transferred and came to live in one of the rooms that had become available in the flat I was in.

We started plotting our escape.

October 2010

After a six month placement, my then boyfriend was offered a permanent position.

Time to flee the overcrowded sub-sub-let hell we were living in and enter the savage London private renting market. A dream finally come true.

After much searching -and here being a tad obsessive and having the capacity to hyper focus on a fixation came in handy- I found a nice flat in a lovely residential street near Westminster Abbey. We moved in and I personally loved not having to fear for my wallet and physical integrity every time I left or came back home for the first time since arriving in London.

Our finances took a hit as we were paying double of what we did in the previous place, but our quality of life multiplied by tenfold as we now had the GP around the corner and access to supermarkets, shops and restaurants within a 15/20 minute walk. My ex boyfriend could walk to his office, which was in the heart of Westminster, and I had a very convenient 30 minute commute with several options between buses and tube.

We lived a stone’s throw from Tate Britain -which I didn’t visit as often as I would have liked to- and St. James’ Park, and in a 30 minute walk would see us in Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly and Covent Garden.

We started going to the Opera regularly as getting home past 6 pm stopped being a life or theft situation. London had indeed a lot to offer and we were now ready to enjoy it as we had at last a safe and nice place to live.

October 2013

When our 3 year contract was up for renewal rent went up by 13%, which had us seriously considered how much we were willing to pay for access to the cultural epicentre of London and living in a safe area.

By that time we also had a better insight into our neighbours and a more realistic perception of the seeming safety we thought we had moved into.

We lived in an ex-council building, one of the early ones, a beautiful red-bricked building dating from the early 1900s and inaugurated by Kind Edward VII as a stone outside one of the lateral walls of the building informed us. Most of the 18 flats in the building were privately owned or rented. Except number 17, the one next to us on the top floor.

Over the years we saw a number of people getting in and out flat 17 and after a while we realised this must be a flat managed by social services, or whatever the equivalent of that is in the UK. Tenants were all different in looks but they all shared a tendency to alcoholism, drug-addiction and questionable friendships.

Getting back home was like opening a kinder surprise and we never knew who we’d find laying on the stairs in several states of consciousness and substance abuse while waiting for whoever the tenant of flat 17 was to come back home and let them in.

Several times I had to climb up through a few dormant bodies whose sweet smell of weed inundated the stairs from top to bottom. In a way it was like having an organic mega-watt diffuser only that the smell made you nauseous as it spread everywhere, mostly inside our flat which could have perfectly passed for a hippy commune.

December 2014

After coming back from Christmas holidays, a few days earlier than my ex, who had gone to Italy to see his family while I went to Spain to visit mine, I found the door of flat 17 gone and replaced by a security door and police barrier tape. The following day, two policemen were mounting guard on the landing and asked me who I was and where I was going.

“I live here, in flat 18. Can you tell me what has happened?” I took my chance knowing the odds were slim.

“We’re not at liberty to disclose that information, miss” one of them responded.

“But I live here, I have a right to know”

The one who hadn’t previously said anything repeated what his colleague had told me and wish me a good evening, which was his way of ending the conversation.

For about a month we had policemen in the landing 24/7. One day someone knocked on the door. A policewoman. She gave me the clue I finally needed to understand what had happened.

Apparently there had been a fight over Christmas and someone had been stabbed and taken to hospital. Our neighbour -who happened to be on parole- was missing since then and the police were posted in the building to arrest him in the event he returned. Could I please let them know if he did? Sure, I said, and closed the door feeling that not even here, in this seemingly quiet area, so close to the House of Parliaments and the epicentre of government, I could have any guarantees of being physically safe.

Still, the convenient location to the flat to London’s centre was essential, especially for me as my work involved attending regular events in the evening, from networking to gala dinners that lasted well past midnight, and at least the neighbourhood was safe, if not our immediate neighbours.

January 2015

One night we were awoke by noises of someone trying to break in into flat 17. We knew, without having to check, that our fugitive neighbour had probably returned after the police had left and was trying to recover some of his personal items from the flat. “Should we call the police?” my ex boyfriend asked “What for? He’s probably going to be gone by the time they get here” and indeed as I pronounced those words half-asleep the door of flat 17 closed suddenly, followed by hurried steps down the stairs.

October 2016

A new rent increase that we tried to negotiate as much as we could based on the incident with the previous tenant on flat 17 and the issues with his substitute, who was even more heavily monitored by social services as we were asked to keep a key of his flat because he often forgot his and it was becoming expensive to call a locksmith.

The reason he forgot his key, we discovered, is because he spent his days mostly in an inebriated oblivious state and when he wanted to get back into the flat and realised he was locked outside, he would just break the glass panel on the door to get inside. Which happened at least once a month.

One night someone knocked on my door at 1 am. I was alone in the flat as my ex was in Italy for a few days and I felt quite scared. It was a young man asking if I knew Gary, the tenant of flat 17, as he was outside the building asking to be let in and come up to my flat to pick up his keys. This young man lived in my building and he was coming home when Gary was outside. I confirmed that I had a copy of his keys and that he could let him in. When Gary showed up to my door, the smell of alcohol preceding his appearance, he was carrying a pack of six beers in his right hand.

I gave him the keys, wished him good night and went back to bed, where I remained awake for hours, questioning where I had failed in life to not be given a nice place to live for free regardless of my contributions to society.

That’s the true welfare state and it was failing me big time as I kept paying taxes like a bloody idiot and half my salary went down the drain in rent for a place I could probably obtain for free if only I tried a bit harder, just like Gary did.

June 2018

After eight years in a not so safe area, and the end of a nine-year long relationship I moved out of the flat and ended up in to North London, in what was a rather scruffy neighbourhood in comparison to my previous one. When my sister came to see the area for the first time her first question was “Is it safe?”

I had the same question myself when prospecting the area and had asked a work colleagued who lived in close vicinity. He confirmed it was a very safe neighbourhood, but I couldn’t ignore that safety often means something different for a man than it does for a woman.

Our perception of the concept is not always aligned as we are not exposed to the same threats and an innocent walk back home, or indeed any activity outside one’s living space, can turn very badly for a woman these days as per Mia Freedman excellent piece Why can’t we go for a f***ing run?

However, the flat I found was in a quiet backstreet lined with trees. While it didn’t have a living room, I immediately felt safe and at home when I visited it, I liked my potential new flatmate, a woman from Naples who offered me a shot of limoncello during my visit and with whom I spent two hours talking. I had a hunch that this was my place.

Besides, the flat was in a small building of only six flats and it was very close to two tube tube stations, so at most I had to walk 7 minutes from either. If push comes to shove and someone follows me, it’s a short run and I think I can make it home, I remember thinking.

It helped that it was cheaper than my previous place, which was a rare find as my search for a new abode revealed figures around £1,000 for a space that could barely fit in a single bed. Obviously the market had changed dramatically since I last moved house.

That was the first time that the economic advantages of being in a couple hit me in the face. But as a newly single woman I had a lot less bargaining power, especially if safety was a priority and so I accepted that if I wanted peace of mind I’d have to compromise on spending more money than anticipated.

June 2019

A year into the flat and zero incidents or threats to my physical integrity and no strangers to be found lying on the stairs.

I hadn’t realised how much mental energy the thought of what I could find when getting back home was taking away from me until I was removed from that scenario.

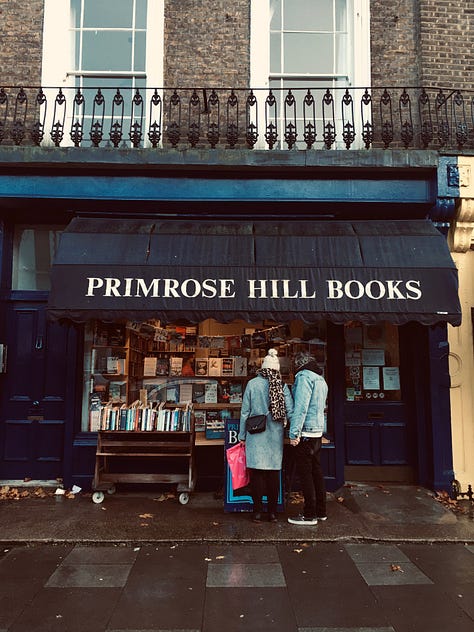

I was enjoying my new neighbourhood, which I found out it offered a lot more than first met the eye, including a yoga studio, bakeries, a lovely independent bookshop and excellent transport links. A highlight was the many and varied live music venues in nearby Camden, from The Blues Kitchen, the Jazz Cafe, the Roundhouse, or the O2 Kentish Forum, all places I was a regular at.

Had I finally found my place in London? I hoped so.

The pandemic years (2020 - early 2023)

While there were many ups and downs, I felt really fortunate and grateful to have moved into this new area as its proximity to green spaces (Hampstead Heath, Primrose Hill, the Camden Canal) and its leafy streets provided a sense of cocoon during the different periods of lockdown.

Thanks to working from home I was able to explore my neighbourhood more often, to fully immerse in it, and I realised I was in love with my surroundings, something I didn’t think could ever happen in London given the city’s cut-through rental market and the pressure it puts on people to move further and further out to areas that trade affordability for your will to live.

A new independent cinema opened during the pandemic as the area around Camden Market was redeveloped and new shopping and food outlets emerged. I started going to the cinema regularly -something I hadn’t done in 13 years- as well as venturing into theatre.

Now

As the threat of a rent increase looms over my head, I’ve been considering how much I am willing to pay to have access to things that make life worth living and that contribute to making me stay sane, curious, spark my creativity and give me a reason to wake up every morning.

But the conversation about rent is intricate with primal emotions and triggers my primal fear of my lack of material safety. I can’t ignore the question of whether it makes sense to keep living in London subject to the whim of landlords when at the same time the chances of owning a flat in this city with inflation through the roof and on my salary (which is both above average as well as ridiculous in the current market) are slim at best if I aspire to live in a decent and safe area.

Prices in my zone reveal that the average 1 bedroom flat is over the £500,000 mark, something that I can’t even put my head around no matter how much I try. The fact that a house in London is more likely to sell above its asking price is not reassuring either.

A quick online valuation of the flat I currently live in reveals it was bought for £140,000 in 2002, a more than decent price for what it is and reflective of its self-containedness (roughly 40 sq metres). If it were to be sold today it’d be short of the half a million pounds mark, regardless its urgent need for a full makeover.

When having the minimum space to move around became a commodity people have to fight over? When wanting to live in a safe area became a luxury?

Who benefits from the narrative that if we want a nice, clean place to live that is not infested by rodents or ridden with mould we need to be willing to put a kidney up for sale in the black market?

To understand how ridiculous the rental situation is in London you only need to watch this video comparing London rooms with European prisons.

ACT II

In her memoir A Life of My Own Claire Tomalin, literary biographer extraordinaire, recounts her move to Primrose Hill in the early 1970s, where she bought a house for £8,000 with the money of the sale of her house in Greenwich (£15,000 k). A stroll around the cosy streets of Primrose Hill and its many gleaming estate agents’ windows informs visitors that they’d be lucky to find a 1 bedroom flat for under a million pounds.

And yet a blue plaque in Chalcot Square, at the heart of Primrose Hill, reveals that Sylvia Plath was an illustrious neighbour. And so was W.B. Yeats, who lived in the nearby Fitzroy Street as well as Friedrich Engels, who lived on Regent's Park Road.

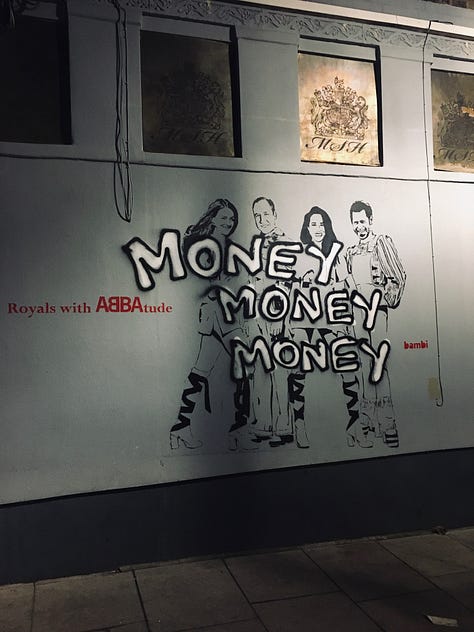

At some point along the line the area ditched its affordability and morphed into a plush and leafy den for millionaire expats, bankers and a handful of extremely rich artists, including Matt Bellamy, lead singer of Muse has his London house there, as I corroborated first-hand when I bumped into him casually chatting to a neighbour outside his home.

The transformation of quiet and to some points even not that exciting residential areas of London such as Notting Hill or North Kensington, into luxury spaces whose safety only the uber-rich can afford is part of Caroline Knowles’ research mapping the epicentres of wealth in her book Serious Money. Walking Plutocratic London.

For the past two decades London has become an attractive destination for Ultra-High-Net-Worth Individuals, who have radically shaped the real estate market and impacted the living conditions of those who work in London on a normal salary and actually live in the city. In 2019 a report by property consultants Knight Frank predicted that in the next five years more people would join the ranks of the Ultra Rich than finish the London Marathon in the following month.

When my sister came to visit over Easter, in the middle of my personal rentgate, she was appalled that rents were not regulated in London, as they are in Paris where she’s lived for 10 years. She’s recently relocated to a small town in North East France as she’s secured a post-doctoral contract in the university of a small town.

The conversation on the lack of rent regulation in London brought back painful memories for her as she was the victim of abuse when the rent cap policy kicked into place in Paris. Her very shady landlady called her to inform her that while she had to put in the contract the cap fixed by the government, which reduced her rent by 200 €, she was of course still expecting that amount to be paid on the side.

When my sister received the new contract with the new rent fixed by law, which she signed and returned, she contacted a housing association, where a lawyer reassured her the landlady couldn’t kick her out as she was dutifully paying her rent as per her contract. It was nonetheless an extremely stressful and tense period where the landlady called her almost daily with threats of sending the police in if she didn’t pay the extra money that only finished when my sister found another place and moved out.

Having a safe place to live is not limited to one’s surroundings, but also to the conditions in which one is expected to live, both physically and mentally as lack of material safety is at the basis of individual wellbeing.

Unfortunately in London both the physical conditions of rented accommodation and the mental condition of tenants have deteriorated over the years as the country has plummeted in a housing crisis, with London being at its the epicentre and a quarter of Londoners living in poverty after paying for their homes and rough sleeping up by 50%.

It could be argued that if one expects to be in a global city this is the price to pay and I’m well aware that the situation in New York or Paris is not very different from that of London, even with a rent cap in place in the case of the French capital.

Or that having access to everything London has to offer comes at a cost and those wanting to benefit from the city’s unmatched cultural scene -London has recently been named the best city in Europe for culture- should be glad to pay a few extra pounds to be able to enjoy its many and varied delights.

But if one is squeezed for money to pay for a place to live in London in order to have access to a cultural scene that is not cheap, with the cost of theatre tickets being the reasons people don’t go to more plays, isn’t that a bit of a chicken and egg situation?

When did living standards start to deteriorate so badly in a city that prides itself on its multicultural diversity and its eclectic mix of people from all walks of life but which offers zero affordable and decent living spaces for those whose presence actually contributes to making of London what it has become to be?

And by that I don’t mean a place for the uber rich.

ACT III

Perhaps another problem of London, and the UK more broadly, is the high concentration of services and cultural spaces into one physical place and sometimes into very narrow areas that increase their desirability and push prices to unknown limits.

A more sustainable solution, besides building more affordable housing (which is about to become a thing of the past as housing associations have warned that higher interest rates makes it financially impossible) and prioritising access to first homes for people who actually live and work in London all year round would be to push the development of more services and cultural outlets in areas currently deprived of them.

What the urbanist Carlos Moreno has defined as the “15-minute city”, a concept which in essence means that most daily necessities (including whether work or leisure) are reachable with a 15-minute walk, bike ride or by public transport. Which has nothing to do with living in enclosed quarters that aimed at keeping us all controlled and policed, as conspiracy theorist have suggested.

Reading the criticism the 15-minute city idea has received over the years (most recently as Oxford ditched the term from its urban planning after backlash from its residents) has left me quite puzzled. I can understand that when the concept landed in British soil people were still recovering from the lockdown confinement and the timing may not have been ideal as they probably took it on the wrong end and thought they were expected to live imprisoned for life, which is not the case.

When I think of the life my family leads back home in Spain, or my sister led in Paris and now in the new place she’s moved to or my own life in my neighbourhood I don’t understand the vitriol against something that, at its bottom, is aimed at improving our quality of life by allowing us to be more connected to the place we live in, instead of seeing it just as a roof over our heads from where we spend two hours a day commuting to a place we can’t afford to live in.

Perhaps it’s a cultural thing as I come from a small place and the city I was living in before moving to London, Bologna, had everything I needed in a 20-minutes walking distance. Besides, for those of us from Mediterranean cultures the fact that people in the UK find normal spending hours on a train to get into work every single day is our personal idea of hell. Why would anyone do that to themselves?

Since moving to my current area I have access to things that even a flat in the middle of Westminster couldn’t provide.

I love spending time in my neighbourhood because it has everything I need -including convenient transport links to get out of it as and when needed and to go to the office, so I don’t feel constraint at all. Quite the contrary. And that’s why a rent increase is such an emotional question for me. Moving to a different area of London doesn't necessarily mean spending less money as the sky is the limit for the rental market these days, but it can mean having to pay more money to get to places I now have within a 10-minute walk.

When Samuel Johnson proclaimed the famous words that “A man tired of London is tired of life” he certainly did so not in the middle of a housing crisis that has been made worse by the cost of living and the increasing number of High-Net-Worth Individuals making London their playground and driving housing prices up and normal people down and out from London’s boundaries.

Dr Jonshon’s words, meant to stress the richness of the London cultural scene and how the city catered to every imaginable taste which could never be exhausted, are therefore in need of an update to reflect the current sentiment of those of us who are becoming a bit disappointed with the downward standard of living and the real cost of having access to London’s cultural scene and a safe, decent place to live, not cut off from essential daily necessities.

Therefore, I suggest that Dr. Johnson’s famous line is updated for the modern XXI London dweller/renter as it follows: A woman tired of London is a woman tired of rent.

Accommodation and neighbourhoods that are not only safe but actually nice to live in and make one feel connected to their surroundings, creating a sense of belonging instead of simply longing for a better life, shouldn’t be the privilege of the uber rich inhabiting the 15-minute cities that have sprung in the past twenty years all over London flooded with shops, supermarkets, bookshops, libraries and GP practices all at convenient walking distance and which go by the names of Primrose Hill, Hampstead, Mayfair, Fitzrovia, Notting Hill, Chelsea and Kensington, or Belgravia.

Epilogue

Despite the above I try not to get discouraged by how relentless the housing crisis in London is and how slim my chances of ever owning a flat here are while paying rent, but at the same time one needs hope in the future to achieve things and London is, after all, the place where many people like me have realised their dreams.

I hope the city and especially the renting market don’t let me down as I still have plenty of things to do and write about here.

Abroad is an independent publication about identity and belonging, living in between cultures and languages, the love of books, music, films, creativity, life in London, and being human in the age of artificial intelligence.

I am glad you survived some "unsavoury" experiences. Looking forward to hearing more about what you do on an evening out in London, so many new places have opened since I left.

Interesting piece. I moved to London in 2012 and lived in a flatshare. The rent was around the area of £600, in Kennington - but it was a double room, me and my then-boyfriend, now-husband shared. We lived with four people. It was...interesting to say the least. Then we moved to Crystal Palace and I was worried about all the things you mention. But in two years there, we never felt unsafe. What we did feel was the that rents were increasing dramatically. So, when our contract ended, we moved to Brighton in late 2016. We were by the sea, in the most fun city ever, and with a cheaper rent. It felt like a huge win! And we do still love Brighton - but it's gotten so, so much more pricey now. In fact, when friends visit and ask about potentially moving here, I tell them the truth: it's the best place ever, but it's getting close to London prices these days. And safety, I'm sad to say, has declined. I was never ever afraid walking home here before the pandemic but I am much more cautious now.

Plus - why why why are all UK flats so damn mouldy? This was never an issue in any of the other cities I've lived in (Moscow, Stockholm, Los Angeles, Florence, or Milan. Well, yes, in Florence a little bit. But nothing like here).