In the past couple of months I’ve had a number of epiphanies about my professional future and AI wasn’t in the picture. Not even remotely1.

But as it’s often the case when you try to run away from something, it often ends up chasing you no matter how far you go. Which in my case was Oxford, where I was hoping not to have to talk about AI during my time there on a Creative Writing course.

I was really looking forward to spending time with people who, like me, had deep appreciation for the written word and how magical and puzzling the process of transforming a vague idea into something that moves people, makes them laugh, reflect, or be inspired is. I was very excited to reunite again with the tutor I had last year when I took a similar course as she showed me how the right tools (in this case writting techniques) can help you achieve amazing results if you know how to use them to get your ideas across on the page in the way you imagine them in your head.

I arrived at Oxford wanting to escape from tech gurus proclaiming that AI, especially when it comes to creative sectors and applications, is manna from the gods.

In particular, I wanted to leave behind the words of Mira Murati in a recent interview where she declared that as a result of the growing sophistication of AI tools some creative jobs will undoubtedly disappear, which is something that has come up in conversations for a while now and already been accepted as part of the trade-off for the new applications of the technology. However, Murati added, maybe these jobs shouldn’t have been there in first place.

Which are my thoughts exactly on the French subjonctif but I understand it still serves a purpose if it’s there. Which one is unclear to me, but I have faith I’ll find out one day.

Murati’s statement didn’t land well with me. Not a time where I had finally decided to give my writing a proper go only to have people like her singing the praises of how AI will boost human creativity by removing functions that help people understand why in order to get B you need to get A right first, and how and why you go about that. My tutor will have a few things to say about that.

Murati may have been tone-deaf on the ripple effect of her words but we can still have hope in the future as long as there’s people for whom an AI script just won’t be acceptable.

I am still of the opinion that AI has many potential uses for good but we haven’t yet untapped its full potential to make our lives better. I can’t wait for the day AI gets rid of tasks that shouldn’t have been there in first place (Murati dixit). For instance, I hope to see an AI that can cook from scratch three delicious meals a day, do laundry (from putting clothes in the washing machine to putting them away, nicely folded), or teletransport us to where we want to go because I’ve had enough of Kentish Town being a no man’s land when it comes to transport links.

However, even in the idyllic setting of Oxford, AI was forced-fed on me at every lunch and dinner as the dreaded “So what do you do for a living?” question was asked each day by a different person who was enrolled in one of the ten courses that were running alongside the one I was doing. I should probably had answered “I exist”, and leave it at that. Instead, I opted for diggin my own hole and mentioned AI. And that was the end of it.

“Oh, how fascinating,” one of my dining table companions exclaimed one day. She was woman from the US and the only reason I can think of why she found AI fascinating was probably because she wasn’t reading the soul crushing headlines that a sensitive, creative spirit like myself encounters on a regular basis. “I bet you must love it!”

“Wouldn’t put much money on that if I were you,” I said as I introduced a massive piece of beef in my mouth as a way to signal that my contribution to the topic was over. I had already reached my saturation point on the subject.

Smiling politely at me, she turned to her right-side neighbourh, a Dutch man who was an Art Historian and was enrolled in a course about Oxford architecture. “Oh, how fascinating. I bet you must love it!” I heard her exclaim. I made the right decision cutting short her prospects of educating herself on a topic she wasn’t remotely interested in.

As I was trying to send down the last bit of the gigantic beef bite I had forced into my mouth to escape a dreadful soliloque about artificial intelligence, I caught another voice, this time from a man seated across the table. “It’s really terrible,” he said, “Students aren’t interested in learning any more, they just want a piece of paper they can show when they walk off here to start making money. And it’s not only in my area. Other colleagues have noticed the same over the past few years.”

When I looked up I recognised the man who was speaking. It was one of the tutors at the summer school programme, a maths professor I had spoken with a couple of days ago as we shared a table for lunch. He had mentioned then that he was also professor at one of London’s top universities as well as a regular tutor on a number of summer courses within his field at Oxford.

“Students are using AI for assignments now and there’s nothing we can do to detect it”, he continued with an air of resignation. “So there you go, you pay for a top level education and then it’s ChatGPT getting the degree for you. I don’t know what’s happened, but it’s hard to get them interested in asking questions these days.”

To his left was Lauren, a native of New Mexico and Director of Technology at a global bank as well as one of my classmates in the Creative Writing course, and who was absorbing every word he said.

“I find that difficult to understand,” she said. “I couldn’t wait to go to school as a child and learn. I guess that means I’m old!” and she laughed openly, producing the hint of a smile on the professor.

“In 30 years I’ve never seen anything like it,” he said with sadness.

A pause to let his words sink in.

“But you work for two Russell Group universities. Aren’t they supposed to have adopted a standard about AI practices?” I asked.

“Yes, we have. But it doesn’t make any difference, to be honest. If people want to use AI, they’ll use it and you can’t do much about it.”

“I heard something recently saying that apparently AI will soon be able to produce PhD level output. Can you imagine what that would mean?” asked Lauren.

It turns out, I can, actually.

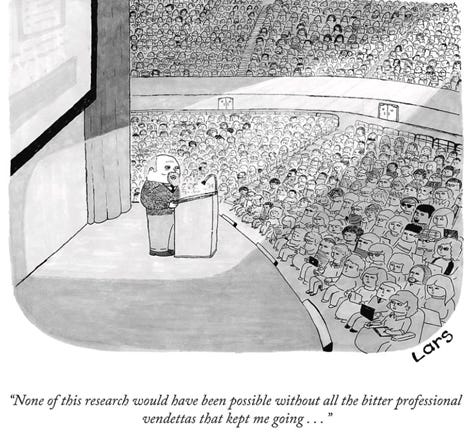

My sister, who is in academia, has fascinating first-hand insights into what’s supposed to be the elite of human knowledge and PhD-level intelligence. After close observation over the years working with the brightest, she’s never witnessed so many adult people throwing tantrums that would shame a 3-year-old. Or to use her own words, “Everyone is fucking mental!”

Of all things AI has in store for us, PhD level intelligence is something I have good reason not to be worried about. At least for now.

“I mean, it’s crazy when you think about it, right? Imagine that you can train AI to provide answers as if it were a first year English student, or a Maths student. Or a non-English native speaker and you ask it to make spelling mistakes on purpose!” Lauren delivered this last hypothesis looking at me straight in the eye. I’m sure it wasn’t personal. Besides, making spelling mistakes and composing rather awkward grammatical structures is what will save me in the future from being mistaken for an AI.

“Oh good lord, don’t give me more work, please!" replied a humoured Mike, whom I hadn’t noticed was also at the table. He was a behavioural scientist from Arizona with whom I had shared a dinner and a great conversation about the Camino de Santiago the previous day, and who was at Oxford following a course on the History of Medieval Cathedrals. “I don’t want to train machines, that’d be the end of me.”

But I understood that the tutor’s complains about AI. And so did Lauren as did Mike, whose comments on the potential of technology to emulate any given level of intellegence or knowledge in its output were an invitation to ask a bigger question: What’s the future of human curiosity?

But of course the conversation I had at Oxford was biased. After all, the people gathered around that table (me included) had all freely chosen to spend their time and hard-earned money learning about things that have no relationship to their line of work nor can contribute to their careers in any significant way. We couldn’t understand who wouldn’t want to spend their holidays like that.

We were, in other words, doing something useless and yet incredibly useful: Indulging in the love of learning for learning’s sake, without any specific goal in mind, without leading to any results or outcomes.

The principle on which the Institute for Advance Study at Princeton was created, to allow people just to think without expecting them to produce results. In his classic essay The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge, published in 1939, Abraham Flexner, one of the co-founders of the Institute for Advance Study, defends this approach and argues that one of the most interesting paradoxes of research is that when fuelled by curiosity, the search for answers can lead not only to the greatest discoveries but also to revolutionary breakthroughs.

An argument that Nuccio Ordine defended in his essay The Usefulness of the Useless (which contains Flexer’s essay), published at the height of the Euro crisis in 2013 as a rejection of the message from the powers that be that the reason why Southern Europe was hit harder was because people insisted in choosing useless university degress that made them unemployable, and therefore more vulnerable to being hit by future economic crisis.

The recent rise of AI, in particularly across the humanities and in creative activities, poses similar questions to the Euro crisis. What’s the point of studying a humanities or arts degree when you’ll have no job prospects as entry level jobs are being automated by AI?

When Mira Murati exclaimed that some creative jobs shouldn’t have been there in first place, she probably forgot that the reason AI has evolved in a way that has made those functions redundant (as well as many career choices challenging) is because AI models have been trained on works produced by photographers, graphic designers, writers, painters, musicians and every one who has ever produced creative work that the technocrats of the Euro crisis urging the Southern Europe youth to study real careers would have deemed useless but which now, in a “how the tables have turned” style, can be conveniently fagocitated by an algorithm in the name of technological progress.

It is fantastic that we have tools to do so many things and encourage us to be playful and enable us to explore our creative side in ways many couldn’t have done otherwise because they lacked the training, or access to it. Technology has democratised sectors that were very elitist, like fashion (thanks to generative AI and 3D visualisation students can now design clothes without actually having to spend a fortune on buying materials) or the media. Isn’t Substack the best example of that?

That is not the question.

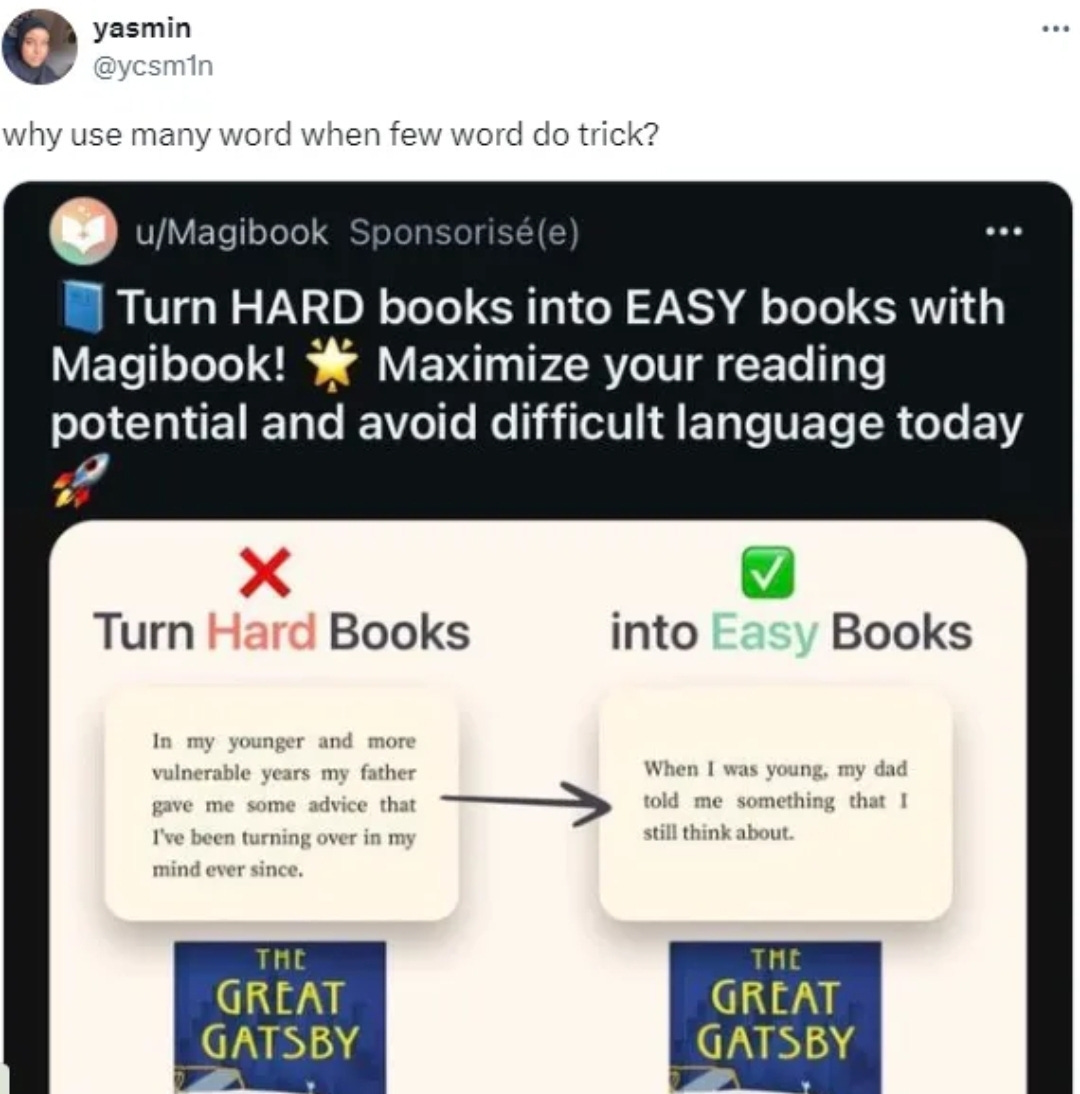

My point is what happens when streamlining a process can impact our ability to understand all the steps that have to be taken along the way to produce a desired outcome. What happens to the satisfaction one feels when learning new skills, whether is drawing, composing music, editing a video, writing, understanding how to capture light in pictures, or learning a language? In removing ourselves from the process and effort of creating something (wheter a film or a sentence in a foreign language) we remove ourselves from the knowledge that comes with it and the critical thinking skills it helps us develop.

Because que je puisse faire quelque chose doesn’t mean que je sache le faire. I told you I’d find the use of the French subjonctif one day.

How can new generations not value the teachings you get from making mistakes and from overcoming the hurdles along the way to enlightment, to mastering something, to gaining a piece of information that would make your soul, if not your pockets, richer and leads to serendipitous findings when you go down a rabbit hole and follow tangents instead of relying on AI to provide answers on demand?

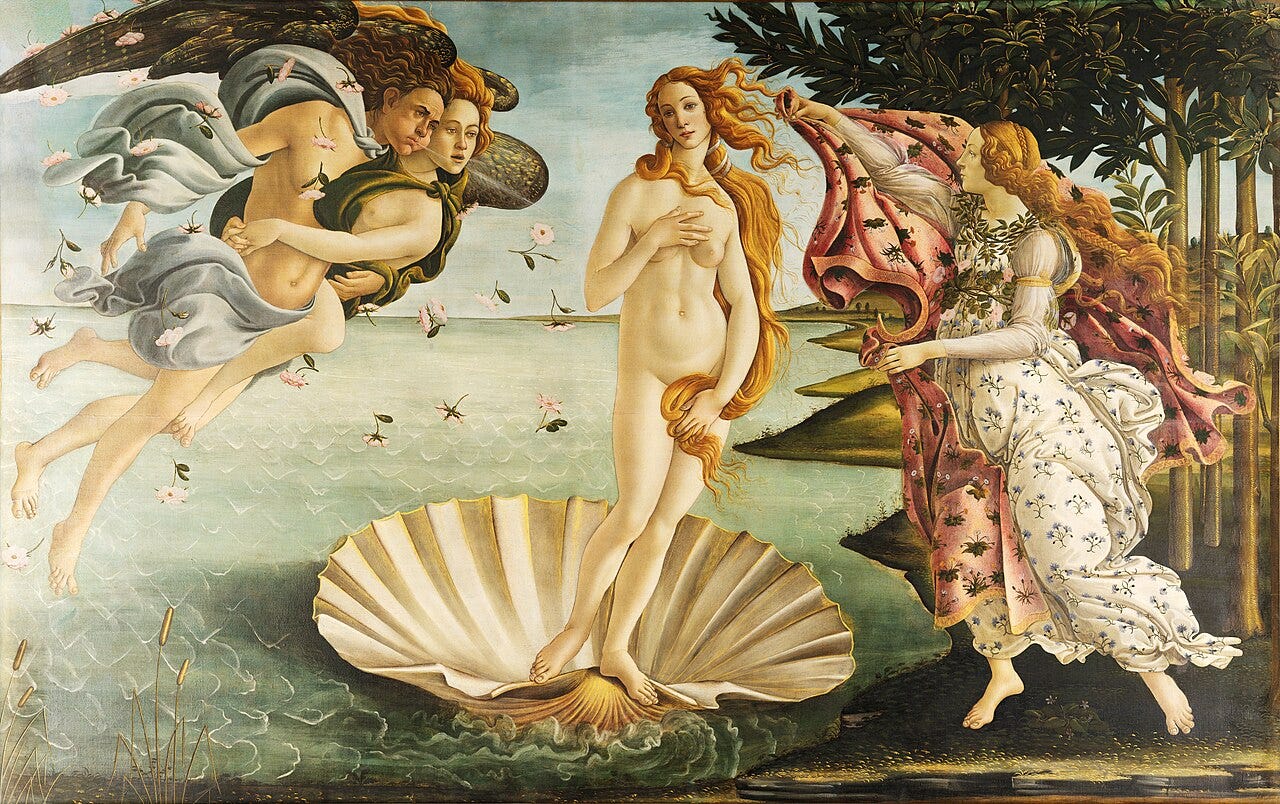

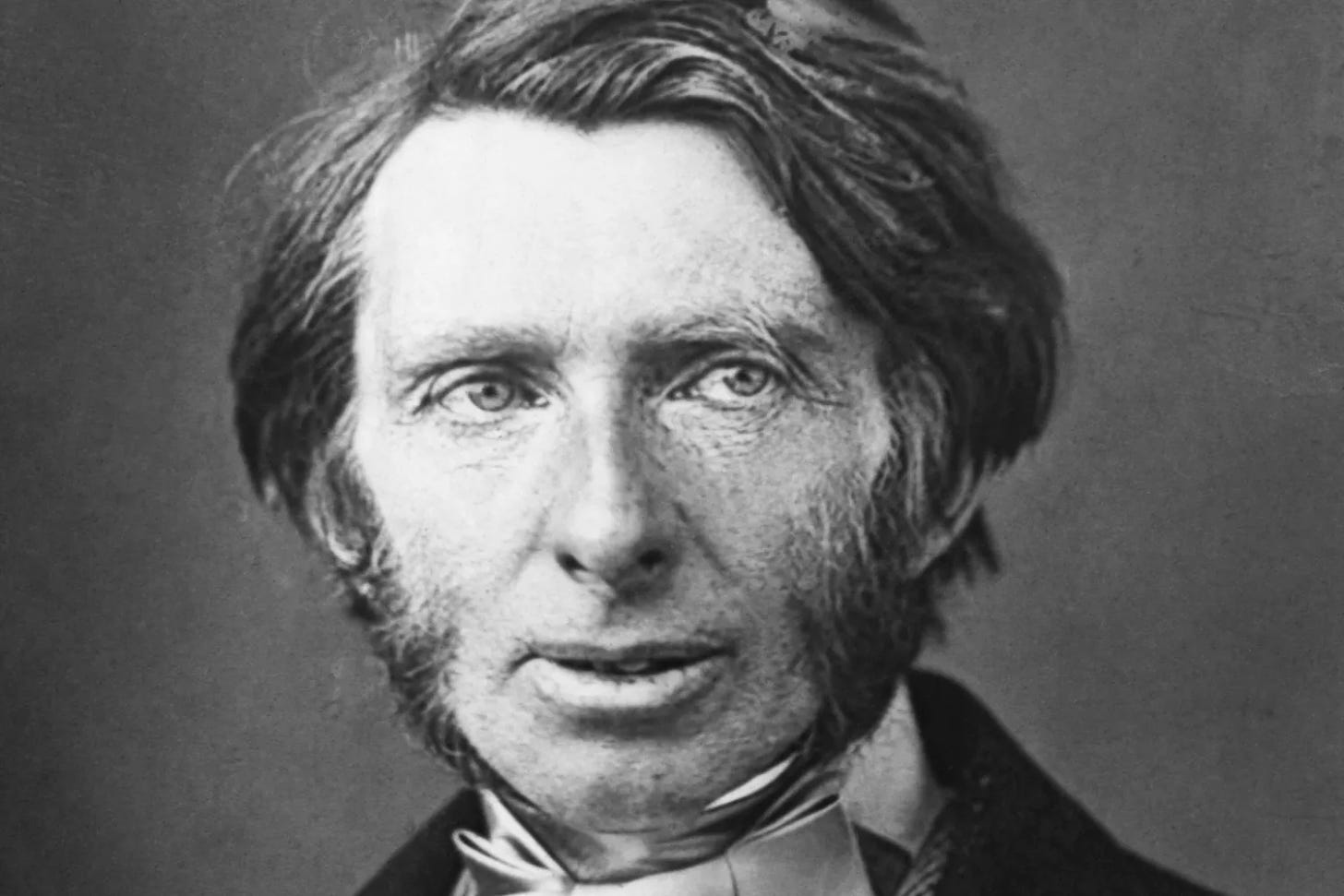

There was a before and after I learned that John Ruskin, the famous Victorian art critic who made the fortunes of J.W. Turner and the Pre-Raffaelites, was married to Effie Grey for five years during which he refused to have sex with her.

Rumour has it that Ruskin’s ideal of the female body was built on the observation of classical statues more than real women, and therefore he admired their smooth marbled shape which happened to lack any body hair. When Ruskin discovered that wasn’t the case of Effie, he was so disgusted that he found sexual intercourse impracticable. Without jumping to conclusions, it’s probably safe to say that Ruskin was not much into women, or sex, and if he was alive today I wouldn’t rule out his pronouns would be They/Them.

How people can live without these totally useless tidbits of information, no doubt the sign of a curious and cultivated mind, is beyond me.

Unfortunately Murati is not alone in her crusade against diminishing human curiosity by simplifying the processes that can contribute to deeper understanding of the steps involved in creative tasks and their outcomes.

In an recent interview Marc Andreesen predicted that AI would potentially lead to a creative renaissance.

One should always take these statements with a bucket of salt.

For you see one of the fundamental aspects of the renaissance, which sprung from Florence to the rest of Europe and which in the original Italian comes from the word Rinascimento (literally rebirth), was a strong focus on the humanities (and man as the measure of all things) and the explosion of the arts, which led to the rising of artistic patronage with excellent results.

This was a period where human ingenuity was at its peak with men like Leonardo Da Vinci mastering both the arts and the sciences and becoming the embodiment of this time of cultural transformation and thirst for knowledge.

A period so fertile in all things arts and culture that the Cardinal Farnese tasked Giorgio Vassari in 1550 to catalogue all the Italian painters, sculptors and architects since Cimbaue and Giotto, both from the XIII century, to their current days. Vassari, who included himself in his magnus opus The Lives of the Artists, ended up producing three volumes, no small achievement, of which became the first history of art work as we understand it today.

Considering that Andreessen is one half of the VC Andreessen Horowizt which, back in November, stated that new rules around regulation on the content used to trained AI models could decrease the value of AI investments if companies have to pay for copyrighted data, of course he is interested in promoting AI as a revolutionary tool that’s going to transform arts and culture thanks to the work others have produced, which hopefully will not be subjected to copyright. And therefore won’t have to be retributed for it.

Call me a cynic, but I have a suspicion that the cultural renaissance he’s talking about doesn’t seem to have either culture, the development of human curiosity or artists’ best interests at its centre.

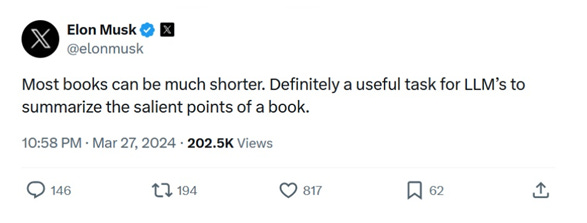

I think what he means by cultural renaissance is more along the lines of the thinking of Elon Musk, who never disappoints with his vision for a brighter future for humanity.

So instead of a fervent thirst for different artistic and scientific disciplines to expand our horizons and foster our curiosity, I’m afraid that in the XXI century we’re stucked with the simplification of knowledge and, by extension, thinking.

Which was the underlaying cause f the pessimism that the professor back at Oxford had displayed when talking about how his students were more interested in monetising a degree than in walking away from their university years with solid critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

And while we can argue that the Midjourney and Sora of today can perhaps pave the way for the artists of tomorrow, it is disheartening to see how AI is transforming every cultural activity into bite-sized, easily digestible, accessible to all content. I am not a snob and I will always defend culture and the arts as a public good that everyone should be able to enjoy and experience, but also understand. At least to a degree in order to fully appreciate their significance and why we must preserve human-made art and culture in the age of AI where more synthetic content is being created and soon will be the norm.

However, in order to understand the impact of removing the creator from the creative process it is essential to be willing to make an effort and push ourselves to think deeper. The problem these days is that even the thinking process is being stripped to the bone and as a result of the rise of social media and the internet we have turned into an effort-avoidant mass when it comes to processing complex information, a skill needed for critical thinking.

Musk may have it his way if we don’t take action because the reading process is the stepping stone to the gate of knowledge and the land of curiosity. Simplifying it means depriving people of food for thought, quite literally.

And it may happen sooner than you think as Rebind, an AI app currently in beta testing that lets you interact with books as you read them, has already enrolled Margaret Atwood, Roxane Gay and John Banville for its AI-bot.

Rebind is born from a noble idea: making books accessible to readers by offering interactive commentary provided by renowned authors but also by university professors. The commentary is recorded and then processed by an AI software that is integrated in every book available on Rebind (selling price about $30 for book; currently the founder is not looking at a subscription model) and with which the reader can chat and ask questions about the characters, points in the story, or aspects of the book they don’t understand.

It’s not the worst idea or application of AI one could come up with, if I’m honest.

But in a world where we have already traded our entertainment for 15 second videos, our relationships for swipes, our communication for whatsapps, what’s left if we also outsource our reading to chatbots that can parrot things back to us instead of letting us figure things out for ourselves? Our critical thinking may end up being compromised. And with it the ability to question tech gurus when they present AI to us as the best thing that could to the future of humanities and culture since the Renaissance.

When Michelangelo was given a massive chunk of marble he didn’t think, “Oh, if only there was an app that could help me sculpt this amazing biblical figure that I have in my head by entering the right prompt!” Nor did Leonardo when he skilfully applied perspective to convey distance in his painting of a mysterious woman.

Their tools weren’t SculptGPT or Perspective.AI. Their tools were a chisel and a brush and I bet that before creating their masterpieces they made a few errors along the way, but eventually one learned how to infuse life into a stone and the other how to guide our eyes to an endless horizon on a piece of flat canvas. Their genius, and the reason we still admire them today, lies in their mastery of the process, not only in the results.

This new cultural renaissance we are supposed to be on the brink of experiencing seems to be more oriented to finally make true the statement, “A five year old could have [insert past participle of your favourite creative activity] done that!” because it turns out that thanks to AI now it’s possible for anyone to become an artist without having to undergo the process that leads to creative breakthroughs.

A few weeks ago I found myself discussing Rebind at an event about AI and Creativity with someone who works extensively with artificial intelligence and I was relieved he had the same reaction I did when I found out.

“But reading is such a personal experience,” he said “and one that allows you to process your own thoughts and ideas in a way that you can make sense of them without distractions. I’m not sure I want to incorporate technology into one of the remaining areas of our cultural life where we can stimulate our critical thinking by challenging ourselves to understand and process the meaning of what we are reading. The whole thing looks like it’s designed to make people lazier, don’t you think?”

His words were music to my ears.

“I mean, isn’t it wonderful when you read a book and then it leads you down a rabbit hole and you go to read another one and come up with the most fascinating discoveries?”

“Oh absolutely, I wouldn’t have found out about John Ruskin otherwise,” I replied.

“Did you know that he didn’t shag his wife for five years? I find that fascinating.”

“I know, right?”

“But do you know why?” he said as if about to let me in into a secret that he didn’t know whether it should be revealed.

Aside from reminding me of Ruskin’s irrational fear of pubes, this conversation made me think of the Oxford professor. I bet his students wouldn’t know the answer nor who Ruskin was despite his strong links to Oxford. What use could that possibly be to them, who studied maths?

Perhaps, I thought while pondering about these questions, I am being very pessimistic about the future that lays ahead for the arts, culture, and human curiosity in the age of AI and I shouldn’t pay much attention to these headlines.

Perhaps Mira Murati and Marc Andreessen are right and we’re on the brink of a spectacular cultural reinaissance by removing unnecessary tasks in the creative process to get to the right output faster.

Perhaps if Giorgio Vassari lived today he could still pen a great catalogue capturing the leading creative minds of the XXI century: The Lives of the AIrtists: from DALL-E and Midjourney to Sora and Copilot.

Or perhaps, and I strongly hope that is the case, no.

Abroad is an independent publication about identity and belonging, living in between cultures and languages, the love of books, music, films, creativity, life in London, and being human in the age of artificial intelligence.

This post is a version of my latests, quite likely last, publication on my tech newsletter The Age We Live in Now.

Oh dear, the apparent decline in intellectual curiosity is sobering - think the pernicious doctrine of utility in education has a lot to answer for; but you've managed to make a disaster narrative great fun to read. I'm also - perhaps unreasonably - slightly optimistic that AI won't end up where people currently expect - heavily based on its total inability to even flog me the books it hopes to sell, based on the "if you bought this, you might like this model." Every time it gets it egregiously wrong, I'm delighted...

Thank you, you have excited me about acquiring knowledge from reading.