Conflict Resolution

On Derry Girls and how a well-timed comedy can be a refreshing and successful portrayal of a complex historical period.

Derry, Northern Ireland. Somewhere around the mid 90s.

A teenage girl named Erin puts on a denim jacket, ready to leave the house on her way to school. Her mother asks where her school blazer is. She responds that she’s not a clone and that she should be allowed to express her individuality because teenagers, she says, now have rights. The mother, unimpressed, asks her husband to pass on the wooden spoon, presumably to test said rights.

Outside the house, we observe a teenager checking the sleeves of her denim jacket. When Erin emerges, Clare, the girl outside the house, asks Erin where her denim jacket is. What’s happened to their plan to be individuals this year? Clare demands. Erin informs her that she had the best intentions, but her mother didn’t seem to agree.

Confronted with the reality of Erin’s defection to rebel against societal rules and emerge as her own person in a world of sameness, Clare quickly reassesses the situation and surrenders with a line that is both brilliant and tragic: “Well, I’m not being individual on my own” she declares as she takes off her denim jacket, the brief marker of her non-conformity with being just another copycat teenager.

The above scene takes place on the first episode of Derry Girls, the hit comedy series created by Lisa McGee based on her own experience growing up in Northern Ireland in the 1990s towards the end of The Troubles, the conflict that for nearly three decades had the Protestan and Catholic population divided and pittied against each other as longstanding historical enmities regarding self-government and British political influence in the region violently erupted towards the end of the 1960s.

Derry Girls, however, is a refreshing take on a complex historical period of time that for the most part has focused on stories inspired by wrongly accused people or those who decided to escape in search of a better future when the violence was unbearable. Films such as In the Name of the Father or most recently Belfast are two successful dramas on what life was like for those in Northern Ireland at the time.

What sets Derry Girls apart is its use of comedy to bring out the historical and political context without being a show about The Troubles per se. When thinking about which formula to use to tell the story inspired by her own experience, McGee has opted to follow the “comedy equals tragedy plus time” formula and it must be said it has produced great results.

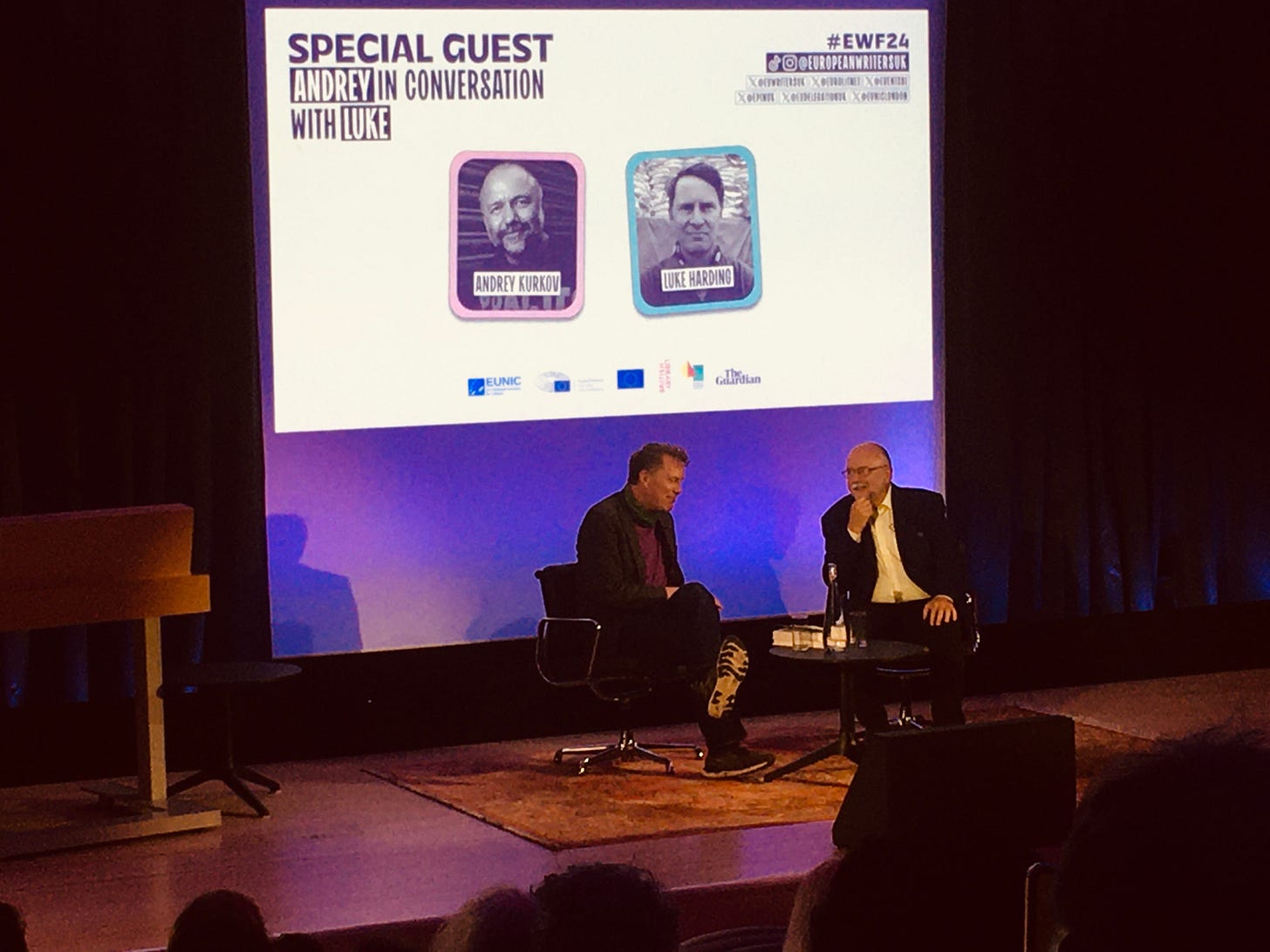

Back in May I attended the Europeans’ Writers Festival in London at the British Library where Ukranian writer Andrey Kurkov was a guest speaker and presented his latest novel, The Silver Bone, a humorous crime historical fiction based on the Russian revolution of 1919.

When asked about his writing process for this new novel and why he had chosen that period of time, Kurkov explained that enough time had gone by for him to write this book in the way he has and which is the first of a series set in the same historical period. He shared that it is difficult to see historical events for what they are when one is a part of them but also to appreciate the absurdities that lead people to fight each other. Expanding on this, he added how he couldn’t carry on writing the second novel of the series after Russia invaded Ukraine. As a result, he focused on keeping a diary narrating the events as he experienced them, which has become Diary of an Invasion.

Kurkov also mentioned that sometimes the best fiction about a key historical event takes time to materialise and mentioned that we’ve had to wait a century to have the best novel about WWI, in reference to Pierre Lemaitre’s novel Au revoir là-haut (The Great Swindle), which he said is the be the best fictional work about the conflict and its aftermath to have been published.

Since I happen to be on page 340 of Lemaitre’s novel, I am going to trust Kurkov on this. I’ll add that I’m loving how the story revolves around two soldiers that after surviving the carnage of the trenches realise his fellow citizens look down on them for not having lost their lives in name of their country. As France is immersed in a celebration of the victims and the building of statues and monuments to commemorate them, the protagonists decide to use that momentum as their reckoning.

Kurkov may be right about how time is a key component in bringing out to life stories and a way of telling them that can’t be rushed, especially around complex historical periods of time where violent conflicts divided people in more ways than we can imagine and events heightened everyone’s sensibilities towards the use of certain words or symbols.

Growing up back in Spain news about the violence in Northern Ireland, were a frequent fixture that preceded or followed news about our very own troubles: ETA, the Basque terrorist group active between 1959 and 2011.

While I didn’t live in an area that was ever directly at risk, the news about bombings across Spain and kidnappings were the background against my generation became of age. Like the protagonists of Derry Girls, we had crushes to cherish, exams to pass, friends to drag along to places only we wanted to go to and big dreams to pursue in between the news of a new bomb exploding claiming a fresh toll of casualties and the crushing of whatever dreams they too had.

We wondered what the future may hold for us when in the summer of 1997 ETA kidnapped and murdered Miguel Angel Blanco as the whole country held its breath and prayed for his release in vain.

It is from that common ground of being a teenager in a place where violence inundated the news, even though not my life directly, that the admiration for the balancing comedic act that Derry Girls is and its ability to be highly entertaining and genuinely fun without being banal stems from.

And it is from that place of admiration that a much deeper reflection has emerged: Can one write a good comedy about a violent conflict without minimising the events nor alienating the victims or survivors on either side?

When in 2017 Bomb Scared, a dark comedy about a peculiar group of four ETA terrorists that are waiting instructions for a mission, hit cinemas the film failed to impress audiences.

The release date (12th October, Spain’s national day) didn’t do the films any favours either and people wanted to boycott the film without having even watched it as they felt it trivialised a very serious matter and considered the comedy was a lack of respect to the victims ETA had claimed over the years.

This was a stark contrast with the overwhelming success of Patria (Homeland) by Fernando Aramburu, a novel published the year before about the life of two families in the Basque country whose lives have been directly impacted by ETA and the rise of violence and which quickly became a surprise bestseller and gathered accolades left, right and centre in an unprecedented way.

ETA would only fully dismantle in 2018 -although the permanent ceasefire arrived in 2010 and was ratified in 2011- so when Aramburu’s novel appear in 2016 it was a shock as silence had surrounded the victims of terrorist attacks in Spain for way too long, adding shame to their often brutal deaths, and the country had only recently started to pay public homage to them and talk openly about the pain the terrorist fight had caused across generations and how it had divided previously close-knit communities.

Patria was so successful because it arrived at a time when people were not only ready to have a conversation about the past, but also willing to understand the other side. Not the terrorist, that is, but those who one day were friends and the next enemies. The novel is human, hard and very uncomfortable at times, makes us question our past and ourselves, and the truths and the lies we are willing to live and die for in name of an ideal, or lack of it. Above all Aramburu’s novel doesn’t take any sides, not it tries to for there are no winners in this conflict, only unwilling victims.

Patria is one of those rare miracles that only fiction can create and which has probably done more for bringing people together in Spain around a very divisive and violent episode of our recent history than any political party ever before.

Bomb Scared, however, lacked the same level of authenticity Patria transpires, which was sacrificed in favour of comedic effect, a rookie mistake considering its subject matter.

In 2017 only six years had passed since the definite ETA ceasefire became a reality. Too little time to cancel out five decades of living in fear for a comedy to touch on the topic right after a phenomenal book had been released and Spanish society started talking about the scars and open wounds without fear for the first time.

Aramburu didn’t pretend anyone looked back after reading his book and thought how absurd everything had been and had a laugh about it. He simply wanted to capture the nuances of a conflict and how it had shattered everyone. How do we live with each other now? is the question readers asked themselves and each other after reading the book.

Bomb Scared had the best of intentions -if you can laugh about your enemy, surely they have lost their power over you- but it forgot a key component from the comedy equation: Time.

To make people willingly revisit a dire situation with a smile, and ideally a laugh, one needs to let the events sit undisturbed for a bit longer and the victims to cool down fully. Then the absurdity of it all will come afloat on its own and it won’t be necessary to point at it because it’ll be obvious. That’s when fiction and comedy can work their magic.

Humour isn’t the path most frequently travelled for stories set in a background of violence for obvious reasons. Even the most adventurous and skilful creators know that wounds take time to heal and attempting to mine through events that have cost innocent lives too soon just for a laugh (literally) can backfire in more ways than one can imagine.

It would have been difficult for McGee, for all her brilliant writing, to get away with making a comedy set Derry in the mid 70s, for instance, when violence was at its peak and disappearances were fairly common.

For audiences to find the humour in such stories trauma must be processed first, many labels have to be disposed of, and people who were directly involved in the conflict must have moved on, either from the ideological stance they adopted back in the day or, in some cases, from the earthly world they used to inhabit. And here is where McGee shows that she has understood the assignment and mastered the laws of comedy.

Setting the series in the 90s, with the hindsight of knowing the Good Friday Agreement was in sight and people were ready to put an end to decades of violent conflict, has helped McGee create an Award winning comedy that has captivated audiences as they follow Erin, Orla, Michelle, Clare and James doing regular teenager things amidst the political and historical context in which they find themselves in.

It bears repeating that Derry Girls is not a comedy about The Troubles, but about a group of young people living during the final years of The Troubles.

The distinction is important because while the show doesn’t try to camouflage the period where it’s set nor sugarcoat it, the comedy works because it comes from the adventures the characters embark on and the problems they inadvertently create and try to get away from, positioning the show as a character-led narrative as opposed to an events-led one.

The capacity of Derry Girls to be so relatable and a highly entertaining work of storytelling, especially with such sensitive material, relies in great part on its well-defined characters and how we can recognise our younger selves in them and the way they react to situations.

These are proper teenagers from the 90s, very naive in many ways but also, like every teenager, confident that they know better than the adults around them. Many of us can see where their actions are leading or identify with the way they react to a situation because we’ve been there and done that.

To the point that when I heard the first notes of Saturday Night in one episode where the girls are at a house party I had the same reaction as Clare and found myself doing the choreography out of the blue while watching it. I have certainly danced to it more times than I can remember.

Choosing to focus on teenagers being teenagers is what has helped audiences around the world find common ground with the show and love it. In fact, the first time I heard about Derry Girls was last year from a girl from Boston that I met in Oxford and who was a massive fan and recommended it highly. She was in disbelief that I lived in the UK and I hadn’t watched it.

If we return to that first episode of Derry Girls, and the scene about the denim jacket, Clare’s declaration about the difficulty of being (an) individual on her own sets the tone of the show and how it intends to portray characters as real people that are transitioning to a phase of their life where they want to assert themselves in the world and be unique, not copycats of any identity trait that may reduce them to mere stereotypes, whether it’s being from Derry, Catholics or girls.

In a way, this is the way McGee is showing the audience that this may well be Derry in the 90s, but this is a story about individuals and not labels.

If the personalities of Erin, Orla, Michelle, Clare and James are distinct and unique, as it’s their way of being and seeing the world. And the same can be said for the adult characters that play a key role in their lives like Ma Mary, Sarah, Gerry, Granda Joe, Uncle Colm or Sister Michael.

The way each of them react to situations that in a drama could easily turn into the catalyst for an explosion of violence, a serious reflection on the complexities of human nature or a tear-jerking narrative about innocent victims and cruel oppressors, in Derry Girls leads to comedy gold as the show masterfully juxtaposes the characters’ personalities to events and situations they find themselves in to great hilarious effect.

When the news anchor announces that John Hume (leader of the SDLP party and one of the main architects of the peace agreement) has called for cross party peace negotiations once again, Sarah remarks that “John’s really dying for peace, like, isn’t he? It’s all he ever goes on about. I hope it works out for him” while next to a window to dry out the layers of bronzer she’s put on. “Aye, I hope it works out for all of us, Sarah” Ma Mary replies.

The threat of violence potentially breaking out at any point is very present in the show as illustrated by the armed patrols inspecting the school bus or stationed at checkpoints across Derry and at the border, but it never becomes overpowering.

Much of the hilarity in Derry Girls stems from the way the script brings together the fictional elements of the story with real events the five main characters find themselves in and how they navigate them to get their way about a situation or get out of trouble.

When in Season 2 the protagonists are getting ready for a Take That in concert in Belfast, the news that a polar bear has escaped Belfast zoo jeopardises their plans. “There’ll be other concerts” Ma Mary says to Erin, which it’d be a normal answer to console a disappointed teenager somewhere else but not in Northern Ireland in the 90s.

Erin reminds her, matter of factly, that it’s nothing short of a miracle that Take That have set foot on Belfast because “nobody good ever comes to Northern Ireland as we keep killing each other” and this is truly their one chance.

So when the girls resolve to take a bus to Belfast without telling anyone, Michelle makes sure they’ll be well stocked for drinks and brings along a suitcase full of vodka. The unexpected presence of their school headmaster Sister Michael -a brilliant interpretation that won Siobhán McSweeney a BAFTA - on the same bus causes the girls to panic and deny the ownership of the suitcase for fear of reprimands.

Since an unclaimed suitcase in a bus to Belfast is not something one takes lightly, a bomb squad is called to the scene to intervene, further derailing the gang’s trip and showing James in disbelief of the extreme situations he finds himself in since arriving in Derry.

When in another episode the group is arrested by the police after inadvertently having assisted in a robbery when entering the school to find out about their exam grades, they are taken to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) station for questioning.

If this were a different show about The Troubles we would know that the combination of RUC and Catholics doesn’t usually end well for the latter. Clare fears they’ll share a similar fate to the Guildford four and the Birmingham six, and will be forced to confess a crime they have not committed, but Orla is more positive and hopes they end up like the A Team instead.

However, what they all fear more than anything is their mothers finding out they’ve been arrested for breaking and entering the school grounds. When the group is asked by Liam Neeson -perfectly cast in his role as RUC inspector- who they want to call for the interrogation to carry on as they are minors, Erin comes up with the perfect solution to bring the interrogation to a halt and gain time.

The next thing we hear, before we see him, is the voice of Uncle Colm (a truly outstanding Kevin McAleer), a character we’ve already been introduced to in Season 1 and who is defined by a dull tone of voice, a remarkable capacity for telling a story without pauses and the ability to wear down any enemy with the combination of both.

Not even Liam Neeson -for all his past cinematic achievements chasing criminals- can emerge victorious from a round of Colm’s relentless monotone stories. Which, as Sister Michael realises after having experienced them first-hand, are actually quite funny if one has the patience to endure them.

In a story set in Northern Ireland religion and divisions between Catholic and Protestants also get the comedy treatment.

An episode in Season 1 gives us an insight into a regular occurrence in Northern Irish life: the Orange Order Parades, a commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne and a great source of controversy due to their nationalistic nature.

We see the Quinn family getting ready to leave Derry and a great fuss is made about leaving as “early and quietly” as possible as many other Catholic families that have already fled the city to avoid any trouble as the parades march through their streets. However, the family ends up trapped in the middle of an Orange March, a far from ideal scenario.

Once more this scene will easily lead to violence in a different type of story. But here, undisturbed by the chaos around them, Michelle decides to use this time when they are blocked and can’t go anywhere to ask Sarah for a tarot reading. The cards reveal that the love of her life is closer than she thinks. “To think I could be staring at him right now” Michelle exclaims dreamily as Orangemen give them menacing looks as they pass by their car.

In the spirit of the show, and in line with how other characters are presented, Sister Michael and Father Peter are two characters that offer us different incarnations of how religion can be approached and lived individually and within a community.

Through the somewhat cynic lenses of Sister Michael, headmistress of Our Lady Immaculate College, we quickly realise that she views religion with great detachment and for her being a nun is just another job, one she may have even chosen out of convenience, not devotion (although she admits that she does enjoy a good statue and is quite partial to one of baby Jesus), as it allows her not to worry about accommodation for the rest of her life, among other things.

Sister Michael may be the voice of righteousness, at least her version of it, but she is also very protective of her students and committed to making a difference in their lives even though it is not always obvious given her preference for sarcasm and snarky remarks as a form of communication.

Sister Michael’s stance on life and faith is tested by the other key representative of religion in Derry Girls: the good-natured and well-meaning Father Peter, a young and attractive priest that wants to bring religion to younger people by presenting himself as an approachable figure. For Father Peter religion is a matter of belief. Not blind, though, because otherwise he wouldn’t be able to look at his wonderful self in the mirror.

Our first encounter with him happens when he is in fact in the middle of a faith crisis and we quickly realise that he is desperately looking for a sign to guide him back to God as he investigates a potential miracle witnessed by the girls. But when it all turns out to be a lie, he is ready to move on from religion and the spiritual life and pursue more earthly interests.

When we reunite with him in Season 2 during a Catholic and Protestant retreat labelled “Peace across the divide” that the girls attend with Sister Michael, he seems to have put his doubts behind and he appears to be a much more grounded person, albeit Sister Michael thinks otherwise and finds him as unbearable as she did in the past.

We will soon discover we needn’t worry about Father Peter as not much has changed inside or outside (his great hair is still great) and that he hasn’t lost an ounce of the vanity that made us wonder why on earth someone like him would want to become a priest in first place.

To kick off the activities of the retreat everyone must get into into Catholic-Protestant pairs in order to get to know each other better. When Orla complains she doesn’t have a Protestant buddy to pair up with, Sister Michael suggests she and James share one as there are not enough Protestants for everyone to go around.

A remark that lays on the table one of the underlying causes for the frequent eruption of violence: Protestants were a majority in Northern Ireland, but a minority on the whole of the Irish soil, while Catholics were a majority in the Republic but a minority in Ulster. Both felt threaten by the presence of the other.

This is illustrated in another episode when a Protestant West Belfast boy, who has waken up in the middle of Derry after having taken the wrong bus from the airport after a weekend partying in Ibiza, is trying to pass as one of the Chernobyl kids that are visiting Derry. Since Michelle has set her eyes on him, she keeps following him around to kiss him, but the poor guy believes he is in danger and out of fear confesses his identity to her.

When Clare, clad in a Union Jack t-shirt that has been met with surprise to say the least by Michelle, enters the room where the Protestant boy and Michelle are, he jumps at her and shouts: “Whatever you do, please don’t slag off the Pope. We’re outnumbered here,” as he holds on to her tightly thinking her an ally.

Little does he know that Clare only wanted to make a statement by wearing that t-shirt but underneath she’s still a wee Catholic lesbian.

The fact that religion -something so entrenched in The Troubles and at the base of many other conflicts since the plantation of Protestants from Scotland in Ulster to undermine the local Catholic population- is treated lightly, mockingly at times, is definitely something that only a good comedy can get away with provided it leads on to an opportunity to reflect about whether religious differences have ever be so insurmountable as to justify oppression and a longstanding violent conflict in Northern Ireland.

A thought that is voiced by Katya, an Ukranian teenager from Chernobyl that as an outsider has a very different perspective of the reality the girls are engulfed in and who cannot understand why people are making such a big fuss about the fact that they belong to different branches of the same religion.

Derry Girls wouldn’t be the same without the wee English fella and honorary Derry Girl, James, who is introduced in episode 1 as Michelle’s born and bred English cousin freshly arrived in Derry from England.

His presence in the show is a clever device to show how The Troubles remained largely ignored by the majority of the British people, who seemed to have forgotten that the roots of the conflict were to be found on their desire to dominate yet another local population that was peacefully minding their own business in their country.

In fact, the confrontations between the Irish and the British go way back and when the group is preparing for a History exam, James admits he can’t tell his rebellions from his risings, and keeps mixing them up. Michelle is quick to remind him why that might be.

And while poor James is English only by accident and by accent, his presence, no matter how polite and well-mannered he is (or precisely because of that) results suspicious in a Catholic and very Irish sounding Derry. Him being a transplant from England is enough reason for people to fear for his physical integrity and justify admitting him to an all-girls school instead of the sending him to the sure beating that would await him upon crossing the doors of the all-boys Catholic school.

However, in a similar way to Katya, James is an outsider in a place that the girls know by heart and that makes of him a privileged observer.

From armed soldiers stopping the school bus for routine inspections, bomb squads appearing out of nowhere, or not understanding why no one calls the police when an IRA man is found hiding in the boot of the Quinn’s car trying to cross the border on the day of the Orange March, James is the audience’s eyes and voice as he asks the same questions we, outside observers from across the world and by extension less familiar with the day to day of how things actually worked, could be asking if we found ourselves in the same circumstances.

It is often through him that we take in the meaning of a situation that the girls know how to deal with instinctively but which for James may result in a faux pas due to his natural naivety combined with his lack of familiarity with his environment, which is often the source of great moments for us as an audience.

Could Derry Girls have been the same show and received the same praise from audiences if it had been created 10, 15 or 20 years ago?

It is hard to say as its creator Lisa McGee would have a bit less perspective and detachment from the days of her own youth in Derry, which would have shaped her writing differently and whether comedy was the best option.

In the final episode of Derry Girls the characters are about to celebrate Erin and Orla’s 18th birthday at the same time that we see them tackle the 30-page document that set out the principles of the Good Friday Agreement and which voters needed to read in preparation for the referendum that was about to be held.

In search of advice, and perhaps a more informed opinion, Erin asks Granda Joe what the thinks. This is one of the few highly emotionally charged moments of the show as through these two characters we witness what the past has been like and what the future might hold.

Joe, despite having being mostly a cantankerous presence for the three seasons and in permanent conflict with his son-in-law Gerry (a saint by all standards and one of the voices of reason in Derry Girls when everyone else’s common sense is thrown out of the window) gives the perfect answer to her granddaughter.

What he thinks, he says, is irrelevant because the future of Northern Ireland now depends on people like Erin, a new generation whose lives may unfold in a country finally living in peace. Erin, however, wonders whether the Agreement is the best solution as the release of paramilitary prisoners on both sides doesn’t seem fair and won’t make anyone forgive the innocent lives that have been lost.

What if, Erin asks, we vote yes and it doesn’t even work.

What if, Joe responds, it does. What if no one else dies anymore. What if The Troubles become a thing of the past that new generations will struggle to believe was even real. What if, John seems to be saying, one day this conflict is so far removed from us at last that we can look back at it and laugh at the absurdity of it all.

Those questions resonate in the mind of the characters as they, one by one, cast their vote on the Good Friday Agreement referendum. What if they can turn the future into a better place for everyone? A happier one, even.

Going back to the words of Andrey Kurkov about how one cannot write fiction about a conflict while one is living through it, I’d argue that one can write fiction while living through a convulsive time but it may not be very good.

As we know, the first novels about the pandemic have already been published but we may not live long enough to read the best novel ever written about that surreal time of our lives. Time needs to work its magic for a story set against a background that has claimed its share of victims to be well received. Too soon and people won’t be interested in revisiting a past they are trying to forget as fast as possible. It has to become a distant memory first before we attempt to revive it.

While Derry Girls is a fictional story based on Lisa McGee’s life, it is also an account of how many people like her came of age at a time where they could have a say about the future they wanted to build and how they wanted their story to be told and remembered.

Not as something to laugh about, certainly, but rather as a period where hope was trumping fear and that was definitely something to smile about. A reality that the three decades that have gone by since the Good Friday Agreement have made possible for many people in Northern Ireland.

In creating Derry Girls and in choosing comedy as the vehicle for it McGee has also shown the world that well-timed laughter can be the best treatment to seal old wounds.

To learn more about The Troubles

In order to appreciate fully the use of some recurrent vernacular in Derry Girls like fenian, provo, prod, or Orange man, or why Liam Neeson gets a grilling from the girls about how many Catholics there are at the RUC, I have resorted to Wikipedia because, for all its incredibly useful information on everything that makes the UK a great country, the Life in the UK booklet that I had to studied in preparation for my citizenship test is a bit lacking when it comes to any reference to The Troubles.

And as a result of my online reading, and significantly more helpful than the Life in the UK booklet, I’ve come across and acquired a copy of “Say Nothing. A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland” by Patrick Radden Keefe.

This is a thoroughly researched and nuanced book that includes material that was available through the now defunct Belfast Project and details the causes and key events that led up to the emergence of violence and the key actors from the end of the 60s to the eventual ceasefire at the end of the 90s, like Dolours Price and her sister Marian, Brendan Hughes or Gerry Adams.

The book won the Orwell Prize for Political Writing in 2019 and it has been announced that a screen adaptation it’s on the making.

Hardly surprising considering the extraordinary storytelling of Patrick Radden Keefe and how he has carefully brought together the intertwining lives and events at the core of The Troubles.

Abroad is an independent publication about identity and belonging, living in between cultures and languages, the love of books, music, films, creativity, life in London, and being human in the age of artificial intelligence.

I'd be interested to hear other views on this, but mine is that comedy on a background of tragedy can be extremely effective. Other examples would include M*A*S*H* (the Korean War), Porridge (incarceration of the prisoners and perhaps also the prison staff), Fawlty Towers (psychological breakdown) and perhaps Some Girls (the struggles of inner-city living). Larry Gelbart once said something along the lines of, "If M*A*S*H* had been set in a Midwestern hospital, it would have been just as funny, but no one would remember it."

Comedy doesn't need a tragic background, of course, but when it has one it can be very powerful.

Interesting! Comedy can be a great tool when things are happening sometimes, if there is a dictator for example, nothing hurts them more than a bit of satire, mocking them. Like Hitler with The Great Dictator. Or more recently, I’m pretty sure Trump (I get that he’s not a dictator…🫣) wasn’t a fan of the SNL skits 😄

But yes, setting a comedy during a time of hardship is a great way for people to learn about it from a human POV, and adds a pathos to the whole thing.